They say that when Gideon was young, he was visited by an angel. This was when he was a pathetic little farmer, beating grain in his winepress so raiding Midianites wouldn’t find it.

The angel greeted Gideon pleasantly: God be with you, Gideon.

Gideon laughed. God be with me? You mean the God that whooped Egypt ten different ways, but can’t muster a single plague against Midian? Because that God can kiss my ice-cold Israelite ass, Gideon said. And he kept beating his grain.

Gideon was out of his mind, no doubt about that. But crazy could be good, like when Gideon’s dad had built an altar for the public worship of Baal, god of Midian and oodles of sinful Israelites. But one morning everyone woke up to see their altar desecrated and smashed to bits. Guess who did that smashing?

That’s right—Gideon. And the people loved him.

Later, when leading the Israelite forces, Gideon marched against Midian with a laughably small battalion to prove a point—what point, I couldn’t tell you. But it was God’s idea, he said. Sure it was, Gideon!

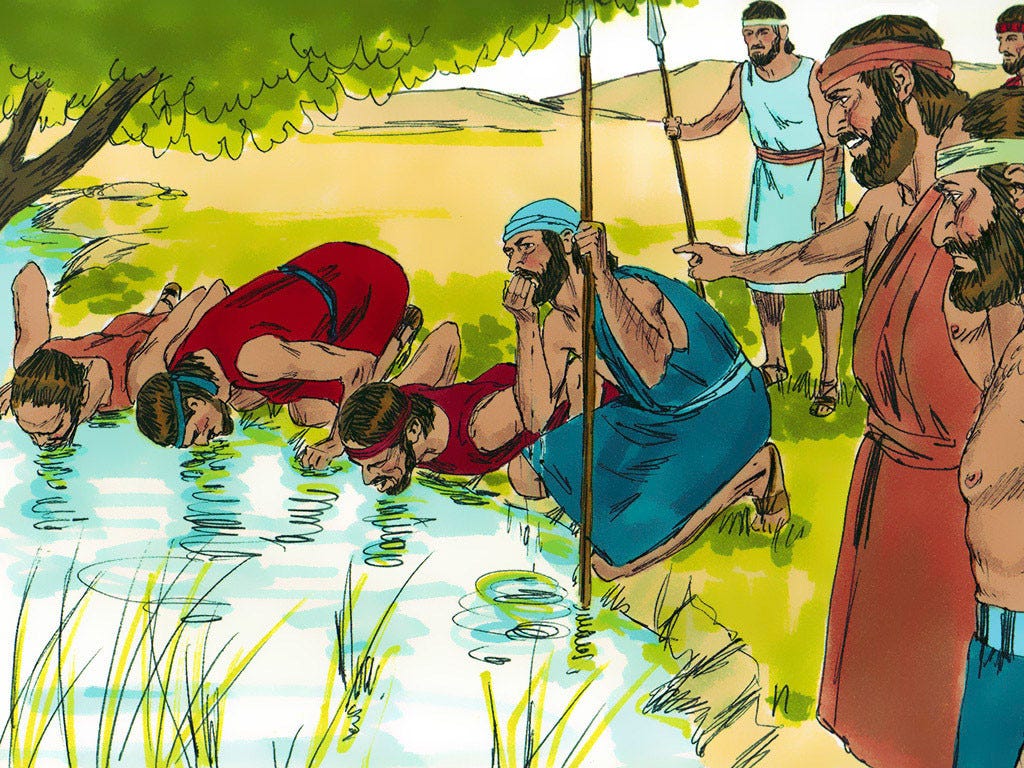

Gideon marched thousands of soldiers to a stream. Drink, he ordered. Nearly all the men knelt and drank directly from the water. But some soldiers, sensitive lads, wouldn’t—they scooped water into their hands and lapped it up with their tongues like dogs, like idiots.

Gideon sent every soldier home except these losers. There were just three hundred of them. And he still kicked Midian’s ass, so there’s your point, I guess.

After the defeat of Midian, several leaders of Israel asked Gideon to be king. Why not, they said, it’s a good deal. You get feasts. You’ll be rich. And many, many concubines. You’ll pardon us for noticing, Gideon, that you have a thing for concubines. He nods.

Plus, they continued, we’ll keep it in the family—your son will rule after you, and your grandson after him…I mean it’s not complicated, this is what literally every other nation does, and it mostly works fine. Meanwhile our leaders are all charismatic lunatics plucked from obscurity—no offense, Gideon. Gideon smiles.

The retinue fell to the ground, showing fealty to the man who would be king.

Gideon at first did not respond. Then he said, remove your jewelry. Take them off, he ordered, the earrings you took as booty. They did so without question. By the time everyone had tossed their prizes onto the floor it came to 1,700 shekels, about 40 lbs of gold.

Then Gideon ordered the jewelry melted and shaped into an ephod, apparently some sort of statue. He placed the ephod on a pillar in his hometown, Ophrah. Nobody knew what it represented or was supposed to mean but Gideon took immense pride in it.

At last Gideon told them, I will not be your king. And that was that.

He retired to Ophrah with this weird pillar and fought no more wars. He lived out his days with dozens of beautiful women and fathered many sons. By the end, there had been forty years of peace from Midian.

But there was no successor, and the people returned to Baal, and Midian was waiting at the gates.

That’s that for Gideon, but before we introduce Abimelech and everything gets messy let’s take care of some business. First, if you enjoy these posts, please share them on Facebook, Twitter, Threads, Instagram, Mastodon, Notes, MySpace, JDate, and Jewkipedia, the secret social network for Jews.

You can also check out the entire Bible for Sickos series, if you are so inclined.

Finally, we’re currently selling a limited number of back issues of the magazine on our shop. There are also shirts and mugs that might make a nice gift for yourself. And don’t you deserve it?

Abimelech was a proud son of Gideon, but his mother was a concubine. Biblical concubines weren’t actually part of the family. Money, security, protection—Abimelech and his mother got none of that from Gideon. Abimelech was raised in Shechem by his mom, not with his father and his family in Ophrah. That can be hard for a kid.

As he grew older, Abimelech showed flashes of his father’s impulsivity, but he had an analytical nature all his own. To his mind, the embarrassment of his upbringing and the troubles with Midian were one and the same. His self-interest and the greater good were thus perfectly aligned, and he could pursue his ends with absolute moral certainty.

So: Abimelech is hosting a party

He has invited all his uncles, leaders of the city, to join. Aww yeah: food, dancing, girls, evil plotting and machinations—this party’s got it all!. And wouldn’t you know it, it’s hosted in the huge tent where Shechem holds their largest, most important, meetings.

One thing we can all agree about Abimelech—he does a nice party. There’s a good spread, dates, hummus, some wine. Everyone is enjoying themselves, but then Abimelech ruins the buzz by standing among his many uncles and making his pitch.

Let me put it plainly, says Abimelech. Would you rather be ruled by seventy sons of Gideon or by one man? A certain local boy?

After some hemming and hawing, the uncles say: what the hell. He’s a good kid and this is the longest of longshots. He’s going to get speared in the face, we might as well help him out. They raid the local temple for 70 shekels—enough, but barely. Abimelech goes to buy himself an army.

The problem however being that 70 shekels does not buy much of an army. So, Abimelech save costs by purchasing the services of cheap criminals and thugs. He hires what the Bible describes as “worthless and reckless” men, then marches these nice fellas straight down to his father’s hometown of Ophrah.

Time to meet the family.

Knock, knock, says Abimelech when he gets to his brothers’ home. When there’s no answer, he calls again. Finally, a distracted brother answers the door. He is annoyed—possibly drunk—until he looks and sees that it’s that kid, what’s-his-name, son of that lady, the concubine.

Hey guys, he turns back and shouts, you’ll never believe who—

SLUICE goes the sword. That would presumably be one of the reckless soldiers, not the worthless ones, but either way it’s a direct hit. The brother falls to the ground.

Now what is all this shouting, says another brother as he approaches. He takes one look at Abimelech, now surrounded by his pirate gang of armed losers. Guys, he shouts, look who showed—

SPLURT. Reckless strikes again. Two down.

The thugs storm the compound and slaughter sixty-seven more brothers: SLUICE, SPURT, SPLORSH, dead, dead, dead, dead.

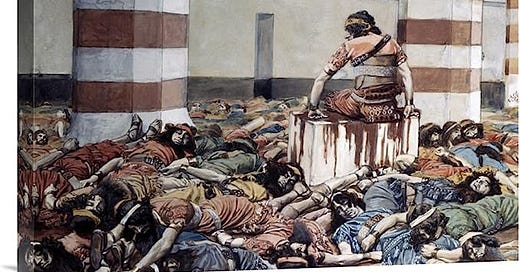

And for $85.61, you can buy an enormous and fairly graphic (extremely kitschy) depiction of this scene on Amazon to mount in your restaurant, synagogue (though it has very Christian vibes), or on the ceiling above your mattress, so it’s the first thing you see when you crawl into bed and when you wake up.

Even as the blood is still wet to touch, Abimelech is standing before a cheering crowd in Shechem. He is under a terebinth, his hands outstretched. The people are chanting his name, and also shouting: LONG LIVE ABIMELECH, LONG LIVE THE KING.

Abimelech, surrounded by his people, smiles. This nation will no longer be led by charismatic lunatics. Long live the king.

• • •

Shechem was supposed to be Abimelech’s capital, the font of his power, but nearly immediately their relationship soured. The uncles and leaders felt dumb that the kid had actually done something with their money, and even dumber that the thing he ended up doing was a war crime.

But at least you can say this about Shechem—they were making up for lost time. Shechem’s leaders and citizens could be heard grousing about their king all over town, and the grousing turned quickly to rebellion.

Abimelech, a student of power, understands. This is normal. It’s just how nations work, what kings do. He instructs his reckless, worthless army to do what they must, even against his mother’s people.

Here is what they do. During the early morning, many citizens leave Shechem’s walls to work their fields. Their farming kept the city supplied with food and drink. Abimelech instructs his soldiers to hide behind trees and rocks, just beyond these fields.

Then, while they are plowing their fields, Abimelech’s general sends the signal. Out come the soldiers.

They slaughter these farmers and salt their land. With salt. Shechem, for a generation at least, is no longer viable for human settlement.

There was another city a few miles away from Shechem named Thebez. The army needs somewhere to go, so they go and occupy Thebez. At this point Abimelech’s army had a well-deserved reputation for violence against innocents, so man, woman, and child take shelter in a large tower at the center of Thebez.

Now, that’s not how you greet a king. Abimelech understands what must be done.

He presses his army up against the Tower of Thebez. The people of Thebez climb higher, up to the roof of the tower.

Abimelech orders them to attack.

A woman on the roof, whose name we don’t know, notices a millstone out of the corner of her eye. She has a wild thought. She rolls the millstone to the edge of the roof, and lifts it far above her head.

She sees Abimelech, standing below. She doesn’t think twice. She launches the millstone.

Down, down, down the millstone flies.

It lands squarely on Abimelech’s head, knocking him down to the ground.

Abimelech, amazingly, is not dead. But he is dying.

Please, he says to his arms-bearer, one of his trusted rent-a-cops. Please, kill me, let me die a soldier’s death, not an ignominious defeat in—

SLUICE, goes the sword. He didn’t have to ask twice.

There was nothing more for anyone to do. There was no cause, no enemy, nothing left to fight for. The soldiers went home. Shechem had gotten what it deserved. The people of Thebez were spared thanks to a nameless woman with a wild idea.

And Israel was simply not yet ready for order and power of this sort, and soon after Abimelech’s death things returned to how they’d been. Their leaders were almost relieved when Israel built altars to Baal, and secretly rejoiced when their neighbors allied against them.

They cried out for a hero to save them—but not for good, not yet.

My years teaching at yeshiva were full of rabbis avoiding these stories, or coloring them in special ways to avoid the obvious. (I taught secular stuff like world history and history of science and conceptual physics and psychology). But when I remarked that Solomon was a monster, a corrupt lecherous dictator, it was met with extreme skepticism and bafflement.

69 brothers ! Any hidden meaning to that number? Talk about virile!