The death of our beloved contributor Sam Gross last week and the blizzard of encomia that followed has got me thinking about what used to be called “Sick humor.” Though Sam produced reams of gags perfectly suitable to the most delicate sensibilities, it’s the Sick stuff for which he’ll be remembered—just as Lenny Bruce will be remembered for the bits that got him arrested, not his Bela Lugosi impression.

To quote Sam’s best-known cartoon, your fancy dinner is someone else’s legs; that is true. Just as Bruce’s acknowledgment of oral sex as a thing that people do is true. At its best, Sick humor can deliver this kind of small truth, it can do a kind of work for our society, in ways that can be hilarious.

But what is Sick humor? Well, it’s a bit difficult to define, but like its first cousin obscenity, you know it when you see it. Perhaps its dominant flavor is an obsession with taboo, especially those relating to the body. Sex, drug use, violence.

Sick humor came of age in the Fifties, the era of the Organization Man and Freudian analysis, Valium and the Pill; its enemy is repression. It seeks “truth” via “honesty,” claiming to show “things as they really are.” All these words are in quotes because they are assertions, articles of faith. Lenny Bruce’s religious belief that everyone is corrupt was, to him, an example of a truth liberated by honesty. And this honesty will, in the eyes of the Sick humorist, lead us to “health.” For this we should thank them, and pay them exorbitantly. (For an example of this kind of thinking, go read this October 1963 article on Lenny in Commentary.)

Sick humor is also about amplification. It is endlessly, purposely over the top. Sometimes this is meant to deliver a satirical payload to a consciousness hardened by layers of national myth, as with Paul Krassner’s “The Parts Left Out of the Kennedy Book.” And sometimes the crassness is the point, as in “The Aristocrats.”1

But for all its coarseness, Sick humor also has a very strong, I would say redeeming sense of egalitarianism. We all shit and piss; we all lust and covet; we all struggle to maintain our status as good citizens in the face of customs, relationships, or even laws that run counter to our nature. Sick humor is fundamentally, foundationally anti-authoritarian. And that’s why it so often uses parody, that peculiar school of judo designed to turn the signifiers of authority against themselves.

What do I mean by foundationally anti-authoritarian? The roots of Sick humor are on campus, in the student humor magazines founded in America around 1870. These student magazines like The Harvard Lampoon and Yale Record were strictly monitored by university officials, so there’s not a lot of overtly “Sick” material in them…until just after WWII. When you combined the elemental stude-versus-prof anarchy of college humor with a generation of men who’d fought and fucked their way around the world, something different, rougher, louder, more nihilistic started to emerge. Chris Miller, co-writer of Animal House, one of Sick humor’s seminal texts, once told me that “Before the war, fraternities at Dartmouth were these guys in jackets drinking martinis. But then you had a bunch of guys in the late ’40s and early ’50s coming to college on the GI Bill who had a fundamentally different idea of ‘fun.’ Those were the first Deltas.”

Maybe that’s why soldiers’ humor became student humor in the postwar period. But why did this souped-up student humor become the national sense of humor? Yes, demographics would’ve made the humor that Boomers liked the dominant flavor, but why did Boomers like this hard-edged Sick style in particular?

Soldiers’ humor is what it is because it has to relieve a very heavy load of trauma in the listener; it needs to penetrate, and dissipate, a great deal of violence, randomness, and fear. This is why it’s so bawdy and fierce—and why it had been confined to the barracks. But three things happened in the immediate aftermath of World War II that traumatized American audiences, and gave them a taste for—a need for—rougher soldiers’ humor. The first was the knowledge of genocide, perpetrated by a supposedly civilized, undeniably “first-world” German nation. The second was the almost immediate replacement of the vanquished Nazi enemy with the new Soviet one; there was no real rest between World War II and the Cold War.

Finally, there was The Bomb. It is not hyperbole to say that, after the Soviets exploded their own Bomb in 1951, every citizen throughout the West—children included—suddenly found themselves dealing with psychological pressures that had previously been restricted to frontline soldiers. And so suddenly mass audiences needed the kind of comedy that helped them process this pressure. Vaudeville just wouldn’t cut it.

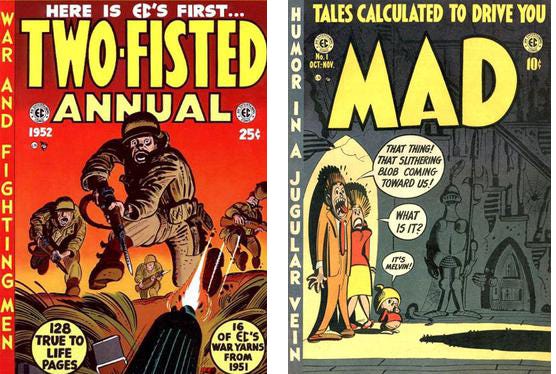

Interestingly, it was children’s media which showed the first signs of this change: MAD Magazine appeared in 1952, itself mimicking a Sunday supplement parody done by The Yale Record in 1949 and surely other comics parodies in other college magazines. What did this have to do with soldiers’ humor? Well, Harvey Kurtzman, the guiding spirit of MAD, had previously edited Two-Fisted Tales, EC’s uncompromising war comic. (Here’s a discussion of Kurtzman’s war comics.)

On the other end of the spectrum, the very adult Playboy appeared in 1954, tracing its own lineage back to Hef’s cheeecake-y college rag, The Illinois Shaft. Playboy would be an outpost of Sick humor for the next 50 years, fostering the careers of everyone from Gahan Wilson to Shel Silverstein and, via the Playboy Clubs, more Sick standups than one could count.

While mainstream comedy imported vaudeville to television, on a hundred nightclub stages rebellion bubbled. It had to—the War had happened, the Bomb was real, and people needed a comedy that could help them process it all. The Pill, too, was real; jet travel was real; America’s vast prosperity was real. Types of comedy that had been worked out on stage in the 20s, performed for radio in the 30s, and put on the small screen in the late 40s and early 50s had nothing to say to these new realities. Once you print fug, it’s only a matter of time before you print fuck. The Lady Chatterley trial in 1960; Catch-22 in 1961…drip, drip, drip.

The history of improv in the Fifties—a form also with its roots on campus, this time at the University of Chicago—has been documented a million times in a million places, so I’m not going to go over it again here. I will say that people like Nichols and May and Jonathan Winters and Joan Rivers were incredibly telegenic, and once Sick humor got a foothold in the culture, it was bound to go farther and farther. And if the Fifties were traumatic to America, the Sixties were even more so. The “Silent Generation” with memories of life before the Bomb was being replaced by kids wondering if they had time to lose their virginity before the first missile strike. “A neighbor boy and I had a deal,” a friend of mine said. “When the sirens went off, we’d meet in my mom’s kitchen.” (Talk about performance anxiety.)

The traumas came thick and fast: A year or so after the Cuban Missile Crisis, these same kids watched Ruby shoot Oswald, live on a Sunday morning. A year or so after JFK Death Weekend, older kids were being called up for Vietnam. The War, the assassinations, these were traumas felt generationally, by a sensitive, self-aware cohort increasingly looking to drugs and the media to tell its story and relieve its pain.

So roughly ten years after TIME released its famous tsk-tsking of Lenny Bruce and others as “Sickniks,” three Harvard boys made Sick humor’s collegiate lineage overt by founding The National Lampoon. In his magisterial Going Too Far—a book you should most definitely read if you’re still reading this—Tony Hendra refers to NatLamp as “over-the-counterculture.” And so it was, until in 1975 SNL upped the ante, turning Sick humor into a purely commercial transaction. Whatever else SNL became later, at its birth it was pure Sick humor. “I would like to feed your fingertips to the wolverines,” said Mr. Mike in SNL’s first cold open. The sketch ends with O’Donoghue’s character having a massive heart attack…which the immigrant Belushi mimics.

Who writes a joke like that? Who thinks a sudden heart attack is funny? People who don’t have them—i.e., young people. Sick humor is great, but it’s a young person’s game, and for all the truths that it can reveal, the revelations brought by old age and infirmity are beyond this style. The clock was ticking.

Sick comedy promised salvation through the appetites of the body, and though Bruce had proven the lethal flimsiness of this idea back in 1966, people like Kenney, Belushi, and Pryor began piling their substantial personal fortunes into pills, potions and powders. Especially powders. It feels unfair to single these three out for doing what all of Hollywood and much of New York seemed to be doing—but the ethos of Sick humor predisposed basically everybody involved. In indulgence is honesty; in honesty there is truth; in truth there is salvation. Right? Helloooo? Can someone please call an ambulance?

Sick comedy could thrive only for as long as there were adults in the room, straights or squares not getting high. Once the addicted rebels were put in charge of things, Sick comedy was dead. Because its premises, as nice as they sounded, turned out to be bullshit. Addiction doesn’t necessarily generate revelation, but it definitely generates more addiction.

The last great shuddering blurts of Sick comedy—things like Ghostbusters, written by Ackroyd for his pal Belushi—kept the game going for a while, but things had changed for good. Looking at Stripes, the 1981 Murray/Ramis/Candy vehicle, you see an uneasy marriage of Sick humor techniques and (of all things!) life in the Army. On the other end of the spectrum there is 1980’s Caddyshack, a sweet coming-of-age story swamped during filming by coked-up Sick humor at its most manic. (Which works, if just barely.) These were transitional pictures, as was Airplane! a wonderful collection of Sick humor gags with nothing whatsoever to say.

These movies might make you laugh, but they weren’t doing any psychological work for the viewer, because the audience’s needs had changed. In the early ’80s, Sick comedy began to be replaced by a different kind, one obsessed with social rules and distinctions. I’m going to call this Propriety humor, where embarrassment or impropriety is the worst thing ever. National Lampoon’s Vacation (1983) is basically the adventures of a white, middle class family confronted by the poors, whether it be the denizens of East St. Louis (who shake them down and strip the family truckster) or Clark’s trailer trash in-laws, immortalized by Randy Quaid in an über-sleazy performance. Though there are profuse lashings of Sick comedy—when Imogene Coca dies, they strap her to the top of the station wagon—there’s another element here, one of class. This had been lurking in Lampoon since the beginning, but now it came out with a vengeance. Poor people, and especially poor black people, are an alien threat, with Beverly D’Angelo’s wife character especially frightened. Compare Vacation’s East St. Louis scene with the John Lee Hooker scene shot on location on Maxwell Street in Chicago in The Blues Brothers (1980), and you see the ugliness in Propriety humor. Both are White fantasies, but in Propriety humor, everyone who’s not “normal” is a threat.2

To use the formulation they drum into screenwriters at USC, “Every movie is about someone who wants something badly and is having trouble getting it”, in Vacation, Clark Griswold is trying to give his family a typical vacation, the birthright of white, middle class suburbanites since 1946…and is constantly being thwarted by an unruly, unpredictable world. “They”—poor people, black people, unfeeling corporations—will not let him take care of his family. The echoes with today’s politics are obvious.

Whatever its flaws (and it had many), Sick humor was egalitarian; Propriety comedy is not. In Animal House, how you acted towards your friends was the important thing, not where you came from. Otter seems richer than Flounder, but is D-Day wealthy? Bluto? Pinto? Inside the frat, everyone is equal—that’s the point. In the world of Animal House, social mobility was easy, good, and happened to the right people. Wherever Bluto came from, he ended up a Senator; the last we see of him, he’s got a beautiful girl on his arm. Because they are true to themselves and others—because they indulge their appetites, acting honestly—the Deltas become life’s winners, on their own terms. The film’s villains, people coded wealthy who act dishonestly, do not. Repressed, conniving Omegas like Marmalard end up working for Nixon and getting raped in prison.

But Animal House’s Sick humor is located in nostalgia, that’s why it works so well. By the end of the Seventies, throughout American pop culture there is a palpable fatigue, bordering on regret, with easy sex and plentiful drugs. Consuming cocaine by the bushel, as if determined to become object lessons, the purveyors of Sick humor are at the end of their ropes. In June 1980, Richard Pryor attempts suicide by setting himself on fire with a freebase pipe. Two months later, Doug Kenney jumped/fell to his death. Eighteen months after that, John Belushi died of an overdose. Harold Ramis leaves Hollywood to kick cocaine. Sick humor, as funny as it is, tends to eat the people who practice it.3 So you can understand why this style had to be replaced.

Whether it was The Preppy Handbook, the movies of John Hughes, David Letterman or SPY Magazine, Sick humor was steadily replaced by a type of comedy that deemphasizes license and rebellion in favor of judgment—taxonomy. “This type of person should act like this, and that type of person should act like that.” This style—which continues to dominate today—indicates a fundamentally off-balance society that is craving stability; it is happy to sacrifice social mobility for intelligible, predictable economic destinies. The teen movies of John Hughes—which I and millions of Gen X teens utterly devoured—displayed nothing if not a taxonomy. “Face it,” Judd Nelson’s rebel says to Anthony Michael Hall in The Breakfast Club, “you’re a neo maxi zoom dweebie.” When Sick elements come into play, they reinforce the social position of the characters; as a lame, ineffectual, unmasculine neo maxi zoom dweebie, Hall’s character is in detention because a flare gun went off in his locker. He can’t even commit suicide right.

This humor of Propriety—I must admit I do not like it. It feels…British to me, in the worst way. None of the eccentricity or whimsy, and all of the judgment; humor as a way to cut down the tall poppies, to keep everyone in their place. Our contemporary comedy is obsessed with social rules and distinctions; what is “cringe” but a hyper-awareness of norms, combined with a teenager’s outsized fear of ostracism? Gen X’s great gift to American comedy, The Onion, is a blend—it uses a fundamentally Sick strategy, parody, and its jokes are uniformly great. But there is an undertone of hopelessness running through it that is pure Propriety humor. Why try? Where you’re born is where you’ll die; the game is rigged from the start.

Sick humor is unruly and emphasizes the things we have in common—the body, love of sex, the ecstasy of drugs, the fear of death. It is fundamentally anti-authoritarian. Propriety humor is about social norms of class and money and region and status—the ways we artificially divide ourselves—so to me it feels fundamentally artificial, and more than a little authoritarian.

This is why Propriety humor is proving so ineffectual against Fascism. The problem with Donald Trump isn’t that he is, famously, “a short-fingered vulgarian.” It’s that he wants to kill you.

But as we trundle off to the abattoir, both ends of the political spectrum prefer Propriety humor; it works for them, if not for us. The left is embroiled in a pointless attempt to scold away sex, greed, and ignorance. To be on the safe side, they’re also deeply suspicious of fun. (Trust me, I’ve tried to write comedy for them.) Much left-leaning humor is morally good but not really surprising—“clapter.”

Whereas there can be some funny stuff produced from a left-leaning perspective—simply through force of numbers—the right is uniformly unfunny. Their patron saint, P.J. O’Rourke, stopped maturing as a Sick humorist the moment Doug Kenney wasn’t there to teach him how to be funny without being an asshole.

The right acknowledges and even celebrates unruly behavior, but wants appetite to be a privilege of wealth and power. “If you help us oppress that other person, we’ll let you do anything you want.” Too many Boomers, brought up on Sick humor, see this offer as a kind of blast from their past. Too many white male Xers like myself, who grew up envious of all the fun Boomers had, see this a their chance to finally cut loose. Everyone else, rightly identifying themselves as the ones who will get it in the neck, are appalled. P.J. O’Rourke’s Republican Party Animal has turned into Caligula.

Propriety humor cannot deal with things outside of/stronger than “the rules,” and so it really doesn’t have an answer for a politician who breaks norms, or some ghoulish compound-in-Montana vision of the future where 78% of us are harvested for our blood. And I think this pressure, this infernal unrelenting pressure, is where the next type of humor will come from. To walk around knowing that some non-zero portion of your fellow countrymen consider you a “useless eater”—that is the kind of psychological distress that cannot help but create a new school of comedy. I suspect its first inklings will be transitional, like The Producers was, addressing the horror of Hitler in a silly way; but then it will come into focus, and (I hope) begin galvanizing a meaningful satirical reaction to our alarming political reality.

Sick humor still exists—after the early 80’s, it went to cartoons. The unreality of things like Ren & Stimpy, or Beavis and Butthead, or South Park, or The Simpsons, Adult Swim, Bojack Horseman, Tuca & Bertie, and on and on, provides a protected space where dark silliness can flourish. And the sheer poundage of content produced—now by all sorts of different kinds of people—gives me hope. Great hope.

Sick humor ran aground because it did not see the poison of addiction; it could not acknowledge that the addict is inherently untruthful, his/her view inherently distorted. Propriety humor, already quite long in the tooth, is failing because it dies not see the poison of status; it cannot acknowledge that the natural endpoint of a rigid social order could very well be slavery, or even genocide.

God, we need something new—anybody know any geniuses? That’s why I am so sad about Sam Gross; we need people like him more than ever. But we will find them, I’m sure of it. I look forward to meeting them.

AN EDITORIAL NOTE: We are going to run an advice column. Please send any questions to publisher@americanbystander.org.

IIRC, that routine has been around since vaudeville. “The Aristocrats” demonstrares that Sick humor has existed forever; what is notable is how this informal, back-room style became what civilians preferred.

Though Animal House touched on a similar beat of racial paranoia—“Mind if we dance with your dates?”—that scene is capped to reveal the Deltas’ fear as silly. “The dates” are shown walking home, footsore but safe; the black guys in the club did them no harm, while the white Deltas did.

(It nearly ate me. The first thing that happened when I nearly died in 2011 was I completely lost the ability to write. And when my comedy writing ability came back about three years later, it was no longer any type of Sick humor.

I’m glad you liked it! I was wearing my Historian Tie.

I know for myself, the comedy I like to write and the comedy I like to view is the comedy of *connection*- people reaching out to each other and failing because of their own hangups, blindspots, and weaknesses, with the catharsis being when they finally climb over those hills. I see a lot of that kind of comedy- even Bojack Horseman contains a lot of it, on its scaffold of Sick Humor. Ted Lasso is practically an archetype of it. An ethos of *We are all flawed, but we're also all we've got*.

Is that the next school of comedy? I don't know, but I think it speaks to a deep yearning in a modern society built on alienation and social media performance.