Ladies and Gentlemen, Lenny Bruce!!

Thoughts on the infamous comedian, and his infamous biographer

[Author’s Note: For the past several days I’ve been cooking on this essay; I think it’s a symptom of my new subscription to The New York Review of Books (motto: “Get ready to fucking read”). It’s a bit of a dog’s breakfast, but I think there’s enough good stuff to post it. I’m not thinking at my clearest—last night I went to Dan Tana’s, an old Italian joint in West Hollywood, and it put me through the ringer. First, they made me stand 45 minutes on cerebral palsy legs, then when we got to our table they gave me the wrong entrée, then gave me a slight touch of food poisoning. I’m somewhat delirious, writing on pure qi; if this doesn’t hang together, blame Dan Tana’s. We’ll hash it out in the comments.—MG]

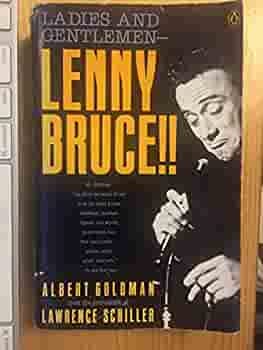

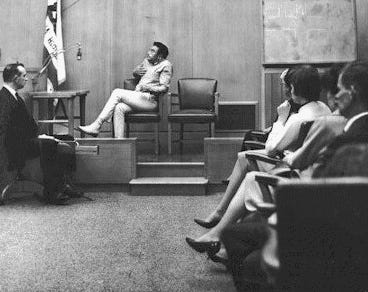

Wednesday night I felt worn down and played out. In such cases there is only one thing to do: put a flock of good words into my head. So I pulled down my copy of Ladies and Gentlemen, Lenny Bruce!!, Albert Goldman’s 1974 biography of the famous standup, and began to reread the 61-page first chapter.

“A Day in the Life: A Reconstruction” is a masterwork of velocity, of facts assembled and gossip collated, of grime and glory at the height of the American Century.

“From the street side emerges a small dark-haired crab-backed fellow. He is handsome in your raffish Broadway manner, like a cat burglar or double-dealing private eye; a nose that looks like it must have been fixed, smooth tan skin, tight curly hair, Arab eyes, and delicate virtuoso hands. Tonight Lenny Bruce will open at New York’s most sophisticated supper club, The Blue Angel, for $3,500 a week; right now he’s having trouble keeping himself from falling on his ass. It’s so cold, so early; he hurts so much inside. He has his fists jammed in the pockets of that black raincoat as if he were cranking up his hips on a set of hand pulleys.”

We follow Lenny, then at the height of his fame, and his gofer Terry, through the lobby of this fleabag hotel into Lenny’s suite—repainted Dufy blue, as are all his suites wherever he travels. The moment the bellhop leaves, the men begin turning the place into an opium den, locking and chaining the door, hiding the drugs in various places (behind the lightswitch—crafty!), putting aluminum foil over the windows. Then Lenny fixes.

“Come on, man, for Chrissake. Bind it tighter. Tighten that thing! Harder! Harder!” Lenny is opening and closing his hand, flexing his wrist and forearm, staring at the back of his hand, the hand of a pianist perhaps, a Toscanini, jerking and flapping, as the catheter tightens, like the death gasps of a halibut…[Later, a] delicate column of blood starts to back up inside the plastic syringe. Lenny’s right. It looks just like the stem of a rose. And there, where it meets and melds with the Meth, is the flower.”

I’m sparing you quite a bit; Goldman’s fascinated by Lenny’s habit, and talks about it at length, in prose both florid and precise. The next pages are lurid, engrossing, funny—but are they accurate? Unclear. Goldman takes plenty of New Journalist liberties, as when he’s discussing Lenny’s love of the bathroom.

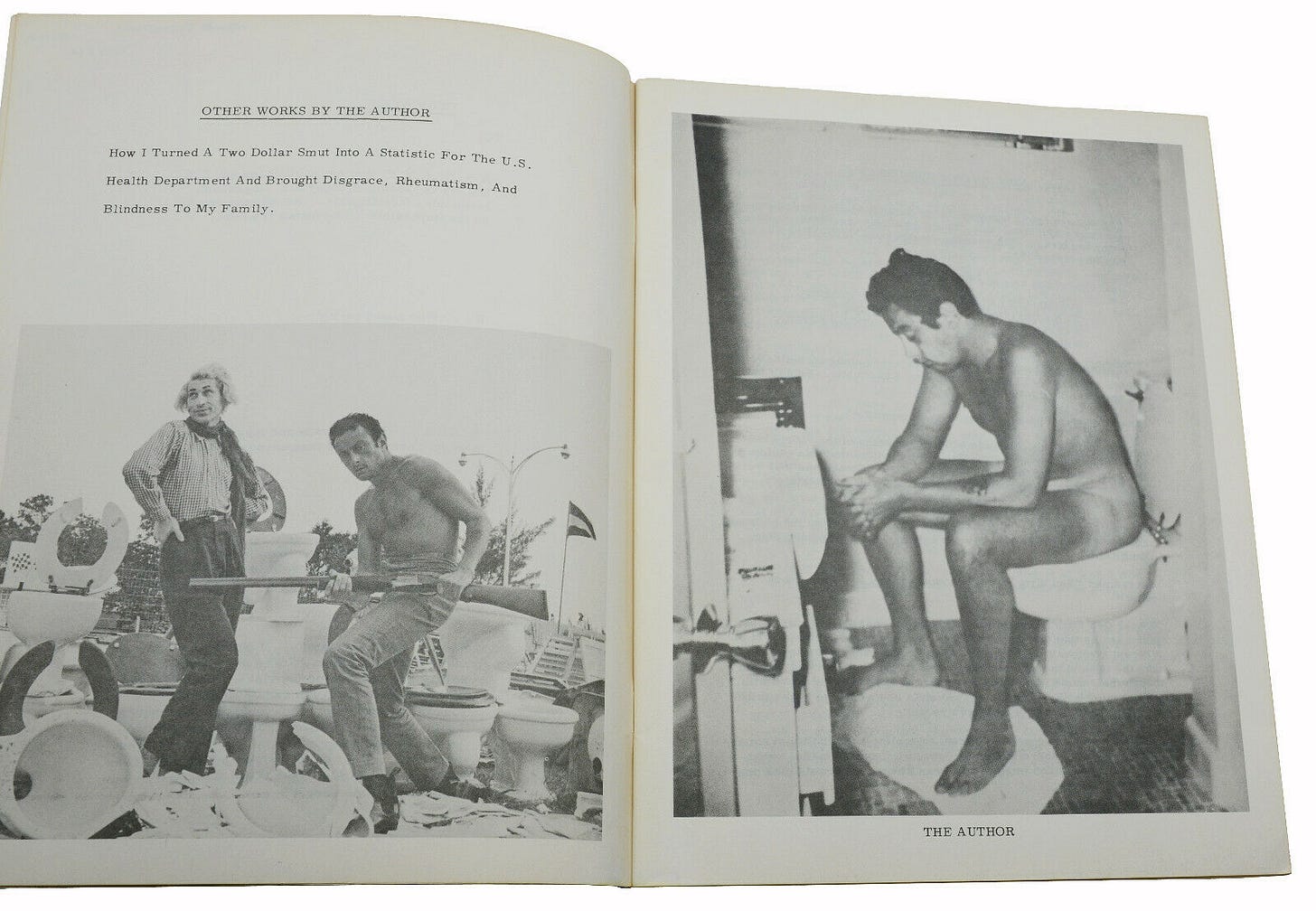

“In Stamp Help Out, the kooky picture and caption book sold at his concerts, Lenny printed a picture of himself sitting naked on the can, head lowered, hands folded, with a funny sort of reflective, pursed-lip expression on his face that spells out the Toilet Thinker, the latter-day Jewish version of the Rodin classic. Actually, his ultimate ideal of pleasure is to sit naked on the can and take out a syringe and pop a vein and shoot and jack and shoot and jack and then maybe have some chick come in and cop his joint or just kiss his mouth—and him all the while dreaming of Honey [his ex-wife—MG] and how she first loved him—and then draw out the syringe loaded with blood and spritz it on the wall where there hangs an Andrew Wyeth picture of a typical American boy, associated in Lenny’s mind with his roadies, all the young, blond straight-looking cats with whom he travels from city to city. Yes, the bathroom means a lot to Lenny Bruce. Cleanliness. Privacy. Fantasy. Ecstasy.”

And that’s just the guy sitting in the john. Goldman’s Mighty Wurlitzer never stops groaning, he is the Bach of Hollywood sleaze. Reading Albert Goldman always makes me feel dirty. That’s why he died so despised; readers resented their complicity. But I have to admit, as pure voyeurism Ladies and Gentlemen is unequalled. It’s Hollywood Babylon to the power of Mommie Dearest.

I don’t read this book often—it’s too rich, too intense. But I genuinely love it, for lots of reasons.

• • •

I’m obsessed with the gap between history and lives as they are actually lived. My instinct is that we don’t learn from history because it doesn’t look anything like the morass of cravings and aversions that make up every person’s day-to-day. The only detail I remember from David McCullough’s Pulitzer Prize winning biography of Harry Truman is that he once came home from a trip and fucked Bess so hard he broke one of the bedslats.

Ladies and Gentlemen is Lenny’s life, warts and all. Mostly warts. And in this way it balances how he’s been turned into history: St. Lenny, Martyr for Free Speech, who was driven to drugs, hounded by the cops until he OD’d. He was hounded, for sure, but…he didn’t kick either.

“Lenny, you gotta take a week off and kick. You’re taking so much now, I’m afraid you’re going to O.D. Each time you go down, you go lower. Aren’t you afraid it’s going to stop your heart, your breathing?”

Lenny’s head is heavy and his eyes are at half-mast. When he tries to talk, the sound rumbles in his throat before his lips part. “Yeah,” he mumbles, “when this gig is over, we’ll go down to Florida for a week and I’ll kick. It’s not hard to kick. I’m done it a hundred times.”

“Have you ever stayed off dope for a real long time?”

“Never more than a week, man. I used to think that I could stop whenever I wanted. That I was stronger than dope. Now I have to say dope is stronger than me…you start off with one or two pills, then it’s three or four, and pretty soon to get that flash, you gotta have a whole handful. An’ shit! Who wants to shoot without the flash? You understand? It’s like kissing God!”

Albert Goldman—because he was an asshole—lays bare a truth that no one, not even today, has read into history: Lenny Bruce was a drug addict moonlighting as a comedian. Whatever else he was—martyr, man ahead of his time, inspiration to other, better standups like Carlin or Pryor—his main job was feeding his habit. Something that, in his mania for truth-telling, he never quite got around to talking about. In a world run by addicts for their pleasure, this bit of clear-eyed assassination is, to me, worth the price of admission.

Personally? I can’t even have caffeine. I couldn’t live for a single day like Lenny Bruce did for 15 years, but man does some part of me want to. Shooting up like Lenny; “eating acid every day” like John Lennon; drinking like Terry Southern or Peter Cook…so many of my favorite artists abuse themselves like this, there must be something there, right? I’ll never know; I am the son of addicts and the grandson of addicts and—it probably goes all the way back to Noah. This book allows me to be a tourist in a place much too dangerous for me to ever live.

I love old movies, and because his prose is so excessive—because he just doesn’t know when to quit—Goldman is incredibly filmic. The page gives you all the details that your eye catches on when you’re watching a film. But unlike say Elia Kazan, Goldman’s movie never cuts away; you hear the swearing. You see the sex, the shooting up. It’s not a modern movie, though. Its like some freaky new version of A Face in the Crowd where we see Patricia Neal doing unspeakable things with Andy Griffith. That version might make a lot more sense than the regular one; instead of thinking, “What does she see in him, anyway?” we’d understand on a visceral level. And that movie, like Goldman’s book, would be an often unpleasant experience, and probably a less successful one, artistically, than Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd.

When I’m reading Ladies and Gentlemen, I’m constantly thinking: Goldman is not great art; he’s probably bad art. But goddamn it, he’s onto something. The question is…what?

Bruce’s career is roughly when the American Century stopped gaining altitude, and started its long descent to today. To steal a metaphor from Hunter S. Thompson—and thank god HST outlived Goldman!—Lenny’s right when the wave crested, paused and started to roll back. I see that in this book.

When I was training to be a historian I focused on inflection points—when did something change? That’s when you really needed to pay attention. And something did change during Bruce’s years—that’s why we’re still talking about him. Was it comedy? Well, strictly from a technical standpoint, sure; but I have a difficult time thinking someone else wouldn’t have done what Bruce did eventually; as Goldman says, the freeform riffing, making the band laugh, slaying the crowd at Hanson’s Deli, had been going on for years.

Today, If you read Bruce’s routines, you’re likely to yawn; even if you peel back the iffy impressions that mar his early stuff, it’s sophomore-year high school wisdom—“Why is the Church rich?” “Why care about what strangers do in bed?” Not wrong thoughts, good ones in fact; but not new ones, even in 1959. We remember Bruce not for the specifics of what he said, which have long been trumped, but because his career encapsulates a fundamental change in our society: the triumph of, and subsequent destruction of, the underground.

When you look closely at Bruce’s big insights, they collapse. It turns out that the n-word is NOT made harmless if a lot of people say it. It turns out that not all men are promiscuous beasts. It turns out that Jackie Kennedy wasn’t “hauling ass” to get to safety as Bruce said, nor was she trying to help Clint Hill into the limo as LIFE claimed; she was actually trying to retrieve a fragment of her husband’s skull. Something much darker and more “sick” than anything Lenny Bruce ever laid down.

So why is Lenny still remembered, invoked? He is excellent shorthand. Beginning right around 1960, then slowly, year by year, mainstream authority abdicates. Bruce did it on stage; ten years later, National Lampoon did it in print. “There was this big door marked ‘Thou Shalt Not,’” Henry Beard once said. “We touched it, and it fell off its hinges.” What was a stable culture balanced on two points—mainstream/underground—became a precarious one, and we’ve suffered with this instability ever since.

Has there ever been a society where the underground swallowed the mainstream? Where the ruling classes adopted the nihilist pleasure-seeking of those with nothing to lose? This stuff is so fucked up in people’s head—even the comedy, especially the comedy. George W. Bush once talked about how he and his buddies used to watch “Animal House” and think they were the Deltas. Today, everybody’s a rebel; an outsider; a truth-teller; a radical; a victim; an addict of some sort or other…and desperately trying to make money off it all somehow. In 2023, we’re all Lenny Bruce.

Lenny Bruce said “everyone is corrupt,” but he had no idea that someone like Trump could become President. An entertainer, openly on the make. A charlatan running grifts just like Lenny used to don a priest’s collar and ask for money. Can a democracy survive without any adults in it, any appropriate authority? I guess we’ll find out. This is an experiment, and a lot of what we go through today are the unfolding results, good and bad, of this experiment.

• • •

In 1925, when Lenny was born the precise ordering of America’s ethnicities and demographics can be quibbled over, it was absolutely clear who was on top: WASPs. Rich, white WASPs ran the country, set the rules and had all the authority. To balance this unjust and intolerable hegemony, there was a well-defined underground that people could escape to (even WASPs)! In the underground, in exchange for not having power outside of culture, you could do pretty much whatever you wanted. What people do in this case is generally pretty standard—free love, some drugs, lots of goofing around—the kind of thing in the first chapter of Goldman’s book. This was completely tolerated, as long as you were in certain cordoned-off zones. Greenwich Village, the wrong side of the tracks, the “red-light district.” When Lenny was doing his act in strip clubs, for example, he was playing by rules as old as Rome. Older.

I think the change might’ve begun in 1919, with the Volstead Act. Prohibition made everyone a criminal, even rich WASPs. Lenny grew up in all that; absorbed it. Everyone drank, but only some people got punished. The goal wasn’t to be moral, upright, good—that was apparently impossible!—but to accumulate the juice, the money, to get away with it.

Fast-forward thirty years and replace bootleg gin with narcotics—with dilaudid or meth, Lenny’s favorites, or heroin, the thing that took him out. Where did the powers that be get off telling anyone what to do? Why should there be cordoned-off areas? Why shouldn’t one adult be able to say “cocksucker” to a bunch of consenting adults, in an adult venue, late at night? We’re all corrupt—why should we hide ourselves? In his heart, Lenny knew why: to preserve the underground, to preserve that oppositional energy that kept him alive.

Lenny got busted, that was completely predictable; but what he did next wasn’t. He kept confronting the justice system. He kept antagonizing the cops, and the Catholics, and the judges. He tried to beat them at their own game…thinking they would accept him if he did.

This is addict-thinking. Stubbornness. Obsession. Doing something terrible for you, but being unable to stop. And it hangs over Goldman’s first chapter like the shadow of death.

Because the exit was right there for Lenny, all the time. If the world really was all corrupt, why participate? Lenny Bruce could’ve stopped performing in 1962; he’d made plenty and said plenty. Like Elvis, he could’ve come back in 1968. He would’ve been on Laugh-In and the cover of Rolling Stone. By 1975, he would’ve hosted the first episode of SNL and had more money than God.

His public comedy takes the very sensible and humane stance that we should judge and punish less, and forgive more. Fair enough. But Bruce’s private behavior tells a different story. He didn’t want to live in the Promised Land; he needed there to be an underground, and he needed to hide inside it. Goldman’s first chapter shows very clearly Bruce’s problem: the thing that made him most uncomfortable wasn’t persecution—that he sought—but acceptance. “You accept me? Well how about now?”

By the time he died in August 1966, free speech was there for the taking. What Bruce wanted was to live like a Village Bohemian circa 1925, by his own rules—but with the power and privilege due a man of respect. He wanted fame, and power, and glory, and sex, and money, and luxury, and drugs, and deference, and personal freedom—limitless personal freedom. But no responsibility ever, to anyone, not even himself. Lenny Bruce was, in this sense, the first modern American.

Poor us.

All volcano jokes aside, I hope you are doing better. That looks like it's out of a cheap horror movie. Hero giblets in gravy.

I just had a fascinating hash-out with a devoted Bruce partisan, my friend Carl--Carl, you made some good points; care to share them here?