[Folks, these are coming slowly these days, because I have been bubbies-deep into a new venture, as well as dealing with the most severe depression of my life. So if I don’t speak to you before Christmas, or whatever flavor of holiday you celebrate, have a very Merry one.—MG]

The Celts believed that Halloween was the time when the living circled closest to the dead—but for me that time has always been Christmas. Perhaps it is my love of A Christmas Carol (which I’ve written about here), or maybe my distinctly Dickensian hope that the afterlife is a cozy place full of good food and shiny trinkets, where everybody is just tipsy enough but nobody is drunk. Since I’m putting up the tree in a day or two—artificial, ever since I became allergic to pine mold—I have been thinking of all those who’ve passed on. Friends, relations, people I knew, people I never did. Of history.

Last night I awoke with the strongest sense-memory I’ve had in years, of being a young man again, walking in Grove Street Cemetery under a light snow, smoking a cigar. Pondering life and death, permanence and impermanence, History and my place in it at age 21, the exact same way I ponder it now at age 54.

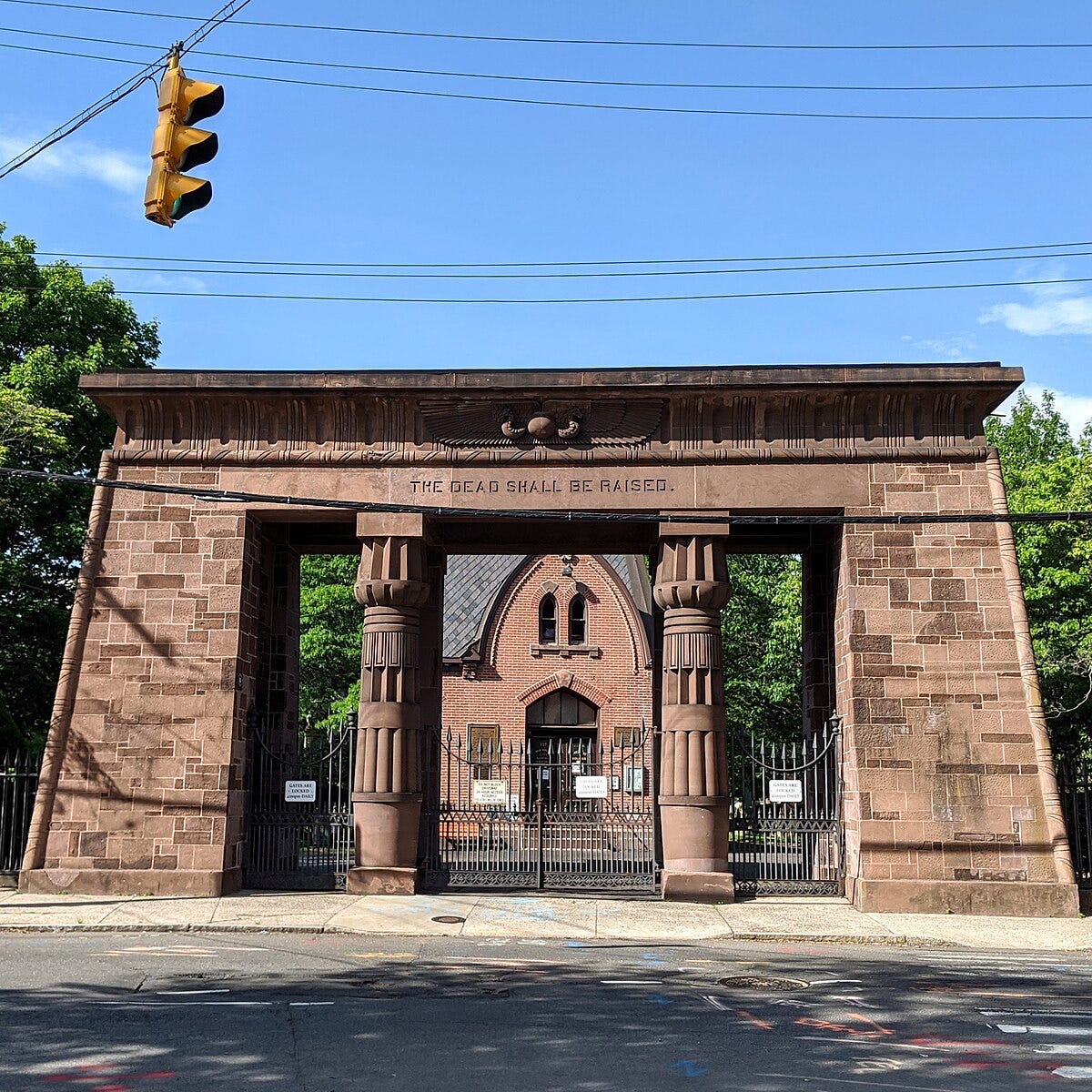

There is a burial ground right smack in the middle of Yale, a city of the dead with streets and intersections, whose brownstone Egyptian Revival gates announce, “The Dead Shall Be Raised.”

“…whenever Yale needs the land,” the joke goes, and though it’s on the National Register of Historic Places, Yale being Yale, and smart lawyers being smart lawyers, I’m sure Grove Street is on borrowed time. The lovematch of some wealthy Ozmandias to the Department of Thus-and-Such cannot be denied, only delayed. But Grove Street Cemetery was there in December 1990, as it still is today, and I had developed an affection for it. It was my habit as a Senior to go walking there at least once a month, looking at the gravestones, seeing which ones were still tended, hunting for the oldest dates I could find. I suppose it was strange in a 21-year-old, but I am both Sicilian and Irish-Catholic and quite hemmed in by the morbidity of my blood. But that year in particular I was not morbid; that year in particular, my life felt like a Saturn V steaming on the launch pad, which was almost unbearably exciting—Where would I be in five years? Who would I be in ten?—and these trips were delicious hours of contemplation, of proportion, of mental rest.

It was right before Finals, and the entire campus was tightening up. You could feel it in the library where the doors were open ‘round-the-clock, in the smoke-stale air of Machine City, Yale’s subterranean misery-pit, and in the dining halls, where the coffee-fueled bullshit sessions were half as long as usual. Everyone was in a hurry to everywhere. I don’t know what it’s like today, 10% more of Yale’s history later, but back then, “Reading Week” was a half-giddy, half grim scramble, where every undergrad tried to cram in all the coursework they’d put off during the semester. I was a fairly diligent student (yes, my parents do read these, why do you ask?) but had a full-time job running The Yale Record, plus my work-study gig.

So that Friday afternoon, I was in desperate need of calm and perspective, something the living could not supply. I gathered up that week’s fistful of dollars earned working in the Yale archives, and walked the four blocks from my dorm to The Owl Shop.

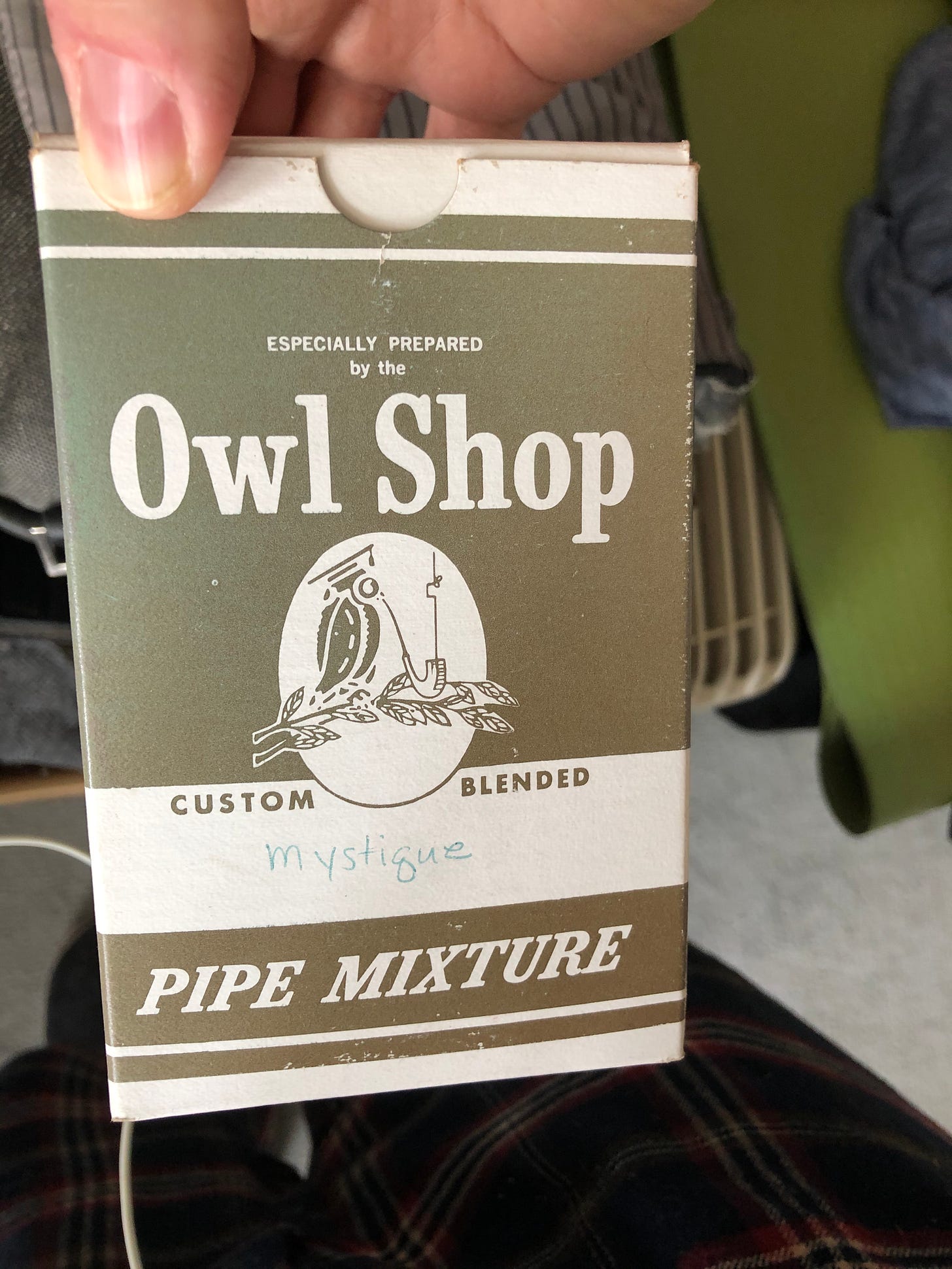

The Owl Shop was, and is, Yale’s campus tobacconist. Here I might make a crack about it being where the Leaders of Tomorrow go to get cancer, but in the 33 years since I left campus, I’ve discovered that people pick up much much worse habits than tobacco, especially Leaders. I’ve always loved The Owl Shop, and not just because they always bought an ad (The Record’s mascot is an owl), though that did help. I still visit it every time I’m in New Haven; it used to be a fluorescent-lit warren of vitrines, walls crammed with preppy “flair,” and (as I remember it) tuff beige industrial carpeting. Now it’s a wood-lined cigar bar, with espresso, top-shelf booze, and leather seats. The old Owl Shop was utilitarian, authentic American Century; the new one is our contemporary fantasy of that time, like Ralph Lauren—gemütlichkeit as channeled by Vanity Fair via The Rat Pack. Needless to say, it’s much nicer; I walked through it last April, and was half-tempted to sit and watch the Yankees game. In the end I didn’t linger because COVID has bequeathed me a tendency to wheeze in the presence of smoke. I was bummed; The Owl Shop’s a hip little joint.

In 1990, however, few students showed up there, and those that did were ones I abhorred—think Brett Kavanaugh or Ron DiSantis, frattish guys craving signifiers of male solidity and wisdom we all knew even then they would never earn. It was for this reason—the signifiers—that my Record staff gave me a pipe and some tobacco when I stepped down as Chairman in May ‘91; I still have it somewhere, with someone’s admonition, “Smoke in good (?) health.” But apart from Yalies trying to act all grown up, the old Owl Shop was mostly older men, New Haveners and professors looking to fill their pipes with in-house blends like “Mystique” and the mysterious “X-3.” Whenever I saw that one, I thought it sounded like “the tobacco that brought you the atomic bomb.” Something serious people used to make their brains go faster.

The streets were slick—from October to April, New Haven is in a constant state of damp—and my sneakers squeaked on the pavé as I opened the door. From behind the counter, Joe smiled at me. Bespectacled, with a forehead that sloped forward from his hairline and a chin that sloped back, Joe always reminded me of S.J. Perelman’s dissolute younger brother. Like SJP, he had the characteristic leanness of a certain type of smoker, something I now associate with the toxin burning through the body’s vitality, driving out the moisture, smoking the flesh like pemmican. But he wasn’t ill; Joe would preside over the Owl Shop for decades more, blending tobaccos as he’d done for twenty-five years before I came to town.

Joe seemed old to me then, but he was likely younger than I am today. He perched, as ever, on a stool behind a long glass cabinet full of Patriarchal bric-a-brac—pewter flasks and Toby jugs, pipes and jack-knives, ashtrays with ducks on them, the set-dec for life as a man in mid-century America. When my wife was script coordinator for Mad Men, I drew on my memories of The Owl Shop to answer some of her questions. Behind Joe were glass jars and wooden cubbies, all filled with pipe tobacco and cigars. In its homeliness, and its bluff sportiness, The Owl Shop was a profoundly male place. Yale had been co-ed since 1969, but in 1990 there were still significant portions of the campus, and the culture, which were the same as it they had been in 1934, when The Owl Shop had opened: Women couldn’t join Mory’s, Yale’s famous watering-hole, and as I stood there talking to Joe, my buddies in Skull and Bones were being locked out of their clubhouse because they’d had the temerity to select some females. (Buckley and the rest of the Russell Trust relented, thank goodness; I heard the whole story from a Bonesman friend this past August. Bravo, gentlemen—I raise an invisible cigar to you.)

Going to Yale in 1990 meant you had to define yourself in relation to that—to its history—and the choice you made, made all the difference. Who did Yale belong to, the black-clad, clove-smoking Lit-Crit majors, or the football team? BSAY and MeCha (the student groups representing African-Americans and Chicanos respectively) or the Societies? Liberal groups dominated a student’s day-to-day; but alums angry since the 1960s had begun to create an entirely separate Yale, fueled by resentment and maintained by defiance, which anyone so inclined could drop into and inhabit for four years, emerging with the bizarre combination of immense privilege and unquenchable grievance that has come to define our political age.

As a disabled kid from a Midwestern public school, I knew Yale wasn’t quite sure about me. But the moment I’d been let in, I’d decided to claim all of it as my own, select the portions I liked, and jettison the rest with extreme prejudice. Deciding to attend YALE, of all colleges, then insisting that your arrival on Old Campus was Year Zero—I never saw the point of that. The history, the context, was what you were paying all that money for; everyone there could succeed on contemporary terms, but could we beat the Old Guys on theirs? And that’s why, after becoming campus Funny Guy, I relaunched The Record.

A friend of mine—the Bonesman who dished the dirt about how they got women in—once teased that my Senior Project for the History major was going to be “pretending like it was 1927.” But he missed the point; I knew there was no place for me in the Yale of 1927. I simply wanted to take the best parts of 1927—and 1947, and 1967—and bring them into 1990. To do that, you had to know the history, and know it on its own terms. Going to Grove Street Cemetery was part of that quest. So was going to The Owl Shop.

Maybe it was my limp, but Joe always remembered me. “The usual?” he asked as I walked in. “Yes, Joe, thank you.” I slid over my $12, and Joe handed me a PUNCH Corona in an aluminum tube—Connecticut and Dominican leaf, Honduran wrapper. Not so big and strong as the Cuban Bolivars I’d later come to love, but a fine cigar, and a fine young man’s cigar.

“Wanna light it up?” Joe laid his hand on a black metal contraption that looked about four times bigger and more sturdy than it needed to be—it was like a Zippo had made love to the Antikythera mechanism. I’ve only seen it one other time, at Nat Sherman’s old smoking room on 42nd Street. Joe pushed some lever, and a spark shot into flame.

“Thanks,” I said, turning the cigar as I puffed it. “Shelving is the mark of a dilettante,” the professor-father of my new girlfriend had instructed me. He smoked these lovely blonde Partagas when he couldn’t get Cubans from his patron Paul Mellon. Seeing how well his life had worked out for him, I’d begun to take pride in the quality of my vices.

Joe turned to help someone else—in the world outside Yale, it was the Christmas shopping season. With a jingly push through the front door I was back outside, into the cold, my breath mixing with the smoke that plumed from my mouth.

As I walked up High Street—past the Bones tomb, then past the Library, where the whey-faced students scurried in and out—the nicotine began to work its magic, both relaxing me and making my mind sharper, more observant. By the time I arrived at Grove Street Cemetery, Reading Week was a dawdle, a formality, and my troubles were gone. Success was assured, both over the next week and in general. I don’t care what anybody says, tobacco’s a great drug.

My reverie deepened as I walked through the great hewn gate. I was happy; I’m always content surrounded by the dead, the building blocks of history. As I crunched through the frosty leaves, I saw both the great and the common; those whose dearest plans had come to fruition, and those whose lives been marred by folly and failure. Which would I be? I thought I knew—but drew such comfort in the fact that, whatever happened, great man or cautionary tale, I’d end up safe and sound in a quiet pretty place like this. History fascinates me, but more than that, it comforts me.

I recognized names that I knew, names of families, great Yale dynasties who’d built the campus and filled endowed chairs. My beloved professor John Boswell wasn’t there yet, but would be, too soon, too soon. Puffing and walking, walking and puffing, I’d read the stones, calculating the person’s lifespan in my head. So many babies and children; so many women of childbearing age.

My favorite spot by far was a set of thin, old-fashioned headstones leaning up against the North wall. Blackened by fire, they were all from the earliest years of the New Haven Colony, that fundamentalist enclave wracked by yellow fever and God’s wrath. These stones had been moved from the New Haven Green in the 1800’s; the bodies, we all knew, were still lurking underneath the sward.

I should say that the Green always strikes me as a grimmer, spookier place than Grove Street Cemetery. I guess it’s all the churches around it? Death doesn’t scare me half as much as people do, especially ones who think they speak for God. We’re seeing that again, now. History shows this particular folly over and over, but you might as well ask it not to snow in December.

The flakes were coming down now, covering zealots and toddlers alike. Having stood at the North Wall, wondering what it would be like to live through an epidemic, my cigar reached its final third—a dangerous time where the smoke grows hot and your head begins to spin. I turned back, and walked more quickly, taking care not to slip. My knees and ankles and hips ached, and my back, and I thought as I walked, “They had aches and pains, too, all of them. Even that one, who was President of Yale. Maybe he had more than most.”

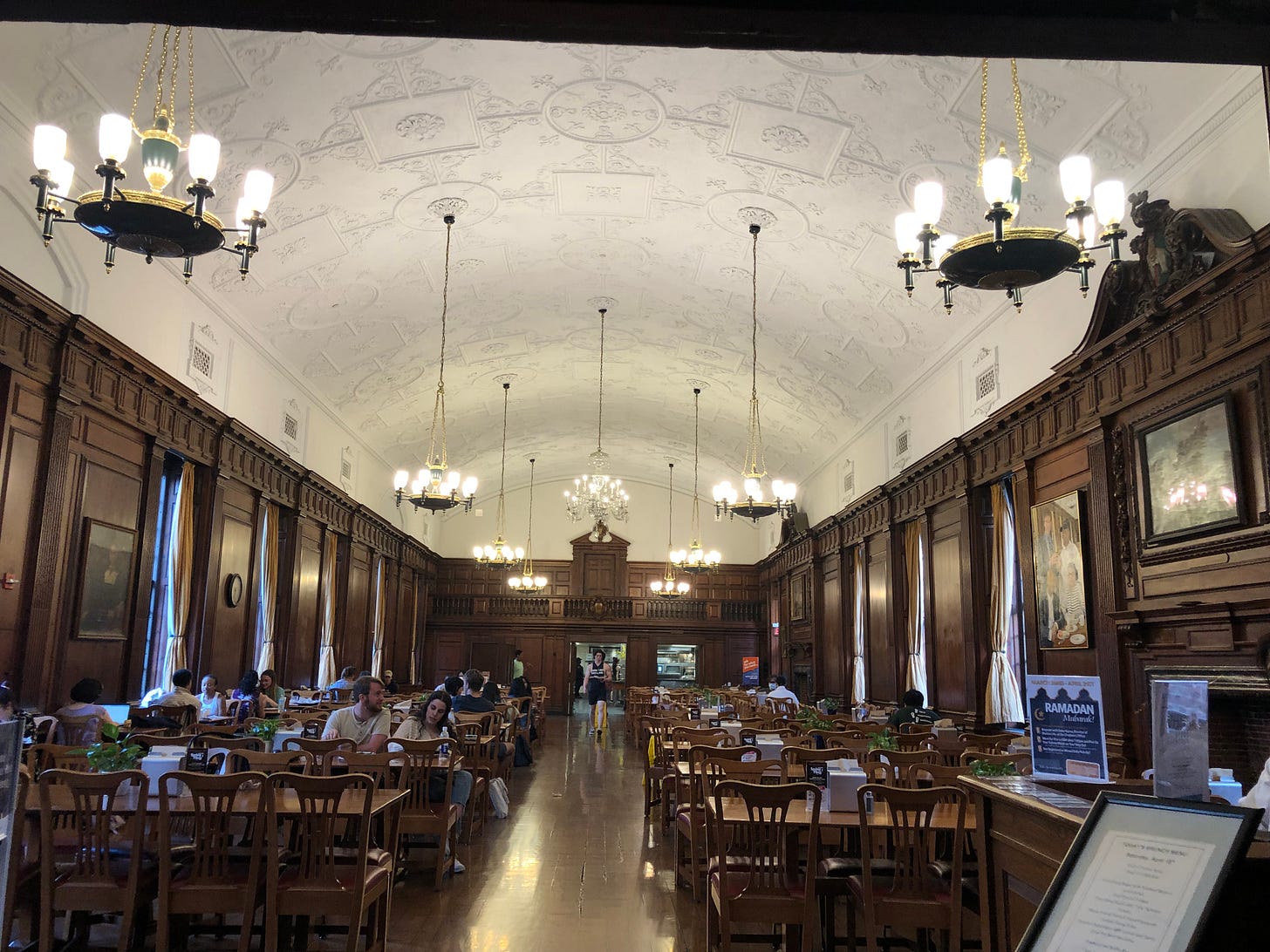

Walking is always painful and treacherous for me, but I did not fall even once. I remember being very happy tromping through that cemetery that day; by the time I got to the front gate it was near dark, and time for dinner. I knew Davenport was waiting for me, a place I loved, warm and bright and full of polished wood, and the smells of institutional food, half-delicious, and half-stomach-turning. And my tall, beautiful girlfriend, the professor’s daughter, so bright and funny, who seemed to extend happiness in every direction. And my future, which I was sure would vault me into something interesting, maybe even History.

A place in History turned out not to happen, but it wasn’t for lack of trying. After the snow thawed and Grove Street turned green, I moved down to New York and presented myself to the machine—books and magazines, as big-time as I could stand—because I thought that was where cultural permanency could still be found. After all, when I walked into The Owl Shop, Joe reminded me of S.J. Perelman, a writer who graduated from Brown in 1928. But History had a trick to play: within ten years of my walk, the digital revolution had taken hold, and writing, especially humorous writing, became the opposite of permanent. Now anonymous teams wrote addictive consumables—first an Onion headline, then a tweet, as habit-forming and forgettable as a cigarette. Not even a fine cigar.

But I didn’t quit. Determined to make history as a major writer of a minor form, I wrote furiously, incessantly, throughout my twenties and early thirties, until Barry Trotter. Nearly all of it has been lost, locked inside MacWord or PageMaker or other proprietary software programs now discontinued, or in the archives of dead publications like The Village Voice. “Do you remember that whole parody of The Learning Annex we wrote?” my old writing partner asked last week. “Or that cold open for SNL with Bill Clinton in the submarine? They even did it for dress, we were so close. God, that still makes me laugh.”

I don’t remember it. I can’t remember any of it, except for the occasional line.

I hate the internet—hate it—because digital media doesn’t last. Offering promises of permanence, it actually destroys. A few years ago, I discovered that all the emails I wrote between 1995-2005—long correspondences between myself and Harvey Kurtzman, Peter Bergman of the Firesigns, Alan Coren of PUNCH, and so many others—were deleted by AOL, which needed the space. Gmail filtered the warning emails into the trash; I guess they needed the space, just like AOL did.

So many years of work, of drafts, of ideas, of everything—gone. Who was I, then? I can only piece it together from dreams, from memories buried under decades of quotidian digital sludge, clues to myself that emerge out of sleep, like the one of Grove Street Cemetery. I hope you’ve enjoyed this essay; someday it too will be deleted, when Substack runs out of money or is purchased by a Nazi billionaire. All that will remain will be whatever I’ve painstakingly printed out on paper. And that will live, here in my filing cabinets, until it, too, is thrown out.

Writers no longer make history; only people like Elon Musk and Donald Trump do, narcissist vandals, people who’ve never had an interesting thought, the worst of us. And the rest of us thrash and suffer like trout on a golden hook, being dragged back into the worst parts of the 20th Century, only this time with nuclear weapons. In 1990, the Cold War had just ended—peacefully. You could’ve convinced me of almost anything. But if you’d told me Fascism would make a comeback, I would’ve double-checked your pipe. Fascism? Are you crazy? There are whole shelves of books; we know what happened last time. A pandemic? Are you crazy? There are whole documentaries about how people fucked up the 1918 Flu. People know; people have learned. Today a friend of mine casually mentioned that they might bring back the Comstock Laws; and of course we all know about Katie Cox in Texas. Women being left to die in childbirth? Fundamentalist theocracy? What is this, the New Haven Colony?

• • •

My grave, whenever it is dug, will not be in Grove Street; New Haven is too cold, and though I love it and its students, Yale is queerly resistant to my charms. I simply could never get interested in making comedy as an addictive consumable. Anyway, my home is here in the sunshine, where anyone not wearing flip-flops is marked out as a scholar. And I will always remember those years, when I was a fueled-up rocket ready to launch.

This week, I turned to my wife Kate and said, “I think I’ve finally found my perfect job.”

”Oh, really? What?”

”I’d like to be a friendly ghost that Yale students pray to during Finals. Especially History students, when they haven’t done the reading. I never did the reading, and always aced the test (my parents aren’t reading anymore). Students would rub my crotch for luck, and make it shiny. Golden. Promise me you’ll pay for a statue.”

”Consider that your Christmas present,” Kate said, and I was happy.

It will be a grand thing to reach across the veil, during Reading Week before Christmas. Perhaps the students will leave me cigars.

As much as the world seems like a giant crap sandwich with a moldy dill pickle on the side, just keep in mind that you learned to weave magic from tobacco and tombstones. The American Bystander is your magic. Great magic to those who know it and know you.

What a delightful piece of writing. Thank you Michael.

I noticed, in one of your replies, mention that you would be wearing a Windsor knot. My wife opines that perhaps a Yale man would opt for a half-Windsor.

I think she makes a good point as a Windsor bespeaks a respect, comfort, and knowledge in sartorial matters, but that a half-Windsor would relate a very subtle insouciance that welcomes the slightest bit of both iconoclasm and a departure from the doctrinaire!