Weasel Question Time #3: What's the Deal with Freshman?

Pershan, currently on Injured Reserve, asks, "I remember that you wrote that novel Freshman. Was that a planned series of four books?"

(This is a series of questions posed to Michael Gerber, Editor & Publisher of The American Bystander magazine, who at five asked his parents to call him “Weasel.” Forty-seven years later, his dream came true.)

Yes Mike, indeed, it was. I used to know the plot of the whole four-book series, but I’ve forgotten it; it’s surely on my hard drive with all my other half-written books. I’ve got a whole YA novel set in ancient Rome, and a James Bond book with a premise so good I’m not going to tell you here, in case I ever do write it.

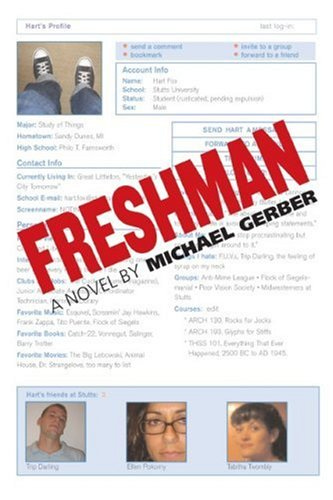

The short answer was that in 2004, I received a $100,000 deal from Hyperion, to write two books set at a fictional Ivy League college. The first one, FRESHMAN, came out in 2006 and tanked so speedily and relentlessly they cancelled the contract. I remember working very hard on it and writing lots of good jokes, but maybe it was just too terrible? I know Hyperion didn’t do any promotion; they seemed to think it was going to be read by college students. (Instead of, obviously, younger kids dreaming of college.) Anyway, when FRESHMAN went toes up, I had written most of SOPHOMORE—back then, I always hit my deadlines—so if I recall correctly, I didn’t have to give back all fifty grand. But I did have to give back quite a bit—maybe $35,000?—and that vast and sudden hole in my personal finances started a slide into illness that nearly killed me. But don’t worry, Hyperion was okay.

It was through such tough lessons that I realized book contracts only obligate the writer. Thank god the deal hadn’t been for twenty million, or else I would’ve bought the Playboy Mansion, then gotten beaten up by Hef when I couldn’t make the payments. “First I’m going to take this Viagra, kid, and then I’m going to beat you to death with my gnarled tallywhacker.”

Where was I? Ah yes, FRESHMAN and SOPHOMORE. Before I give you the long answer: please don’t buy these books. I’d rather read them aloud to you via phone. Even though they have been out-of-print for many years, thanks to the magic of book publishing Hyperion is still claiming to own the rights to both of them, and I will receive no money for any sales. In a Hefnerian dick move, they have somehow removed my self-published edition of SOPHOMORE—something that I negotiated in the severance—and linked that Amazon page to…nothing. Adding insult to blunt force trauma, they claim an illegal Kindle edition will appear this June 14, my 54th birthday.

Who says corporations don’t have a sense of humor?

[“But wait,” you ask, “didn’t you have an agent looking out for you?” Indeed I did, at a big New York agency. And a $400/hour publishing lawyer, too. Why, then, am I subject to, fully 17 years later, such blatant fuckery? Who knows? Love of the game? I loved writing books, and I love readers. But the more I dealt with big book publishers, the broker I got. God bless, god speed, please just go out of business already and quit bugging me. The Ghost of Hef is hovering outside on my balcony, and he looks…engorged.

Because I can’t help myself, I’m working on a memoir; maybe I’ll put it out under our new Bystander imprint. Or publish it here, in chapters, behind a paywall? What do you think?]

Now, for the long version of the story.

First came Barry Trotter and the Unauthorized Parody, my spoof of the Harry Potter books, which I self-published in 2003. Unlike today, this was not low-hanging fruit—quite the opposite. People were terrified that anyone who dared parody Harry Potter, the publishing phenomenon of our age, would be sued into Patronus fewmets by J.K. Rowling. Or, more likely, Warner Bros., who had purchased the movie rights and was gearing up to make Daniel Radcliffe a star. (You know him as Weird Al.)

This utterly offended me; on the one side, the bullying, and the other, the cowardice. So I stepped into the breach. I had to. It was a matter of principle and besides, I was extravagantly broke. The only valuable things I owned were seven Let It Be-era bootlegs and a cat.

Also: I was about to get married, and when Kate, too, said, “Publish it!” I knew I’d picked the right gal.

In my twenties and early thirties, I had a bit of the crusader in me. Perhaps I still do, but back then, it was intense. Among other Articles of Faith, I wanted to make the world safe for longform print parody. Not general parody like The Onion, which was admittedly hilarious, but spoofs of specific originals. In 2001, if you’d taken me out for a—warm water and potato chips? I couldn’t eat much—I would’ve skeined out something like this: “As religion has weakened, pop culture has become our shared mythology. These new pantheons, owned and managed by corporations, have captured more and more of our imaginations. In Ancient Rome, we would be writing poems and plays parodying the Gods to speak to the controversies of the day. Today, we need to be able to parody corporate properties, things like Disney and Marvel and Harry Potter, because that’s what we have in common. Pop culture parody is the only comedy that everyone will understand. And in books, it doesn’t exist.”

“But wait,” you say, “isn’t parody protected speech?” Yes…and no. Settled law doesn’t prevent someone from suing you. Before Barry Trotter, though its legality was beyond question (thanks Falwell v. HUSTLER) print parody was becoming functionally impossible. To get into bookstores, you needed to be published by a Big Corporate Outfit, and any B.C.O. was vulnerable to nuisance lawsuits from whichever other B.C.O. had produced the thing being parodied.

B.C.O.’s guarded their IP jealously, with maximum paranoia. I saw it differently; I believed—and still believe—that modern parody is best understood as a way committed fans deepen their connection with an original. While a parody can (and should!) be critical of an original, it doesn’t aim to destroy the original’s appeal or authority, but establish a more nuanced, timely conversation with it. I had crawled around the carpeted cubicles of Manhattan making these points for about a decade, garnering absolutely no success and some enmity. By the time I was writing Barry Trotter in longhand on the Belmont bus, trekking to and from work at a “reading is GOOD for you” children’s magazine, I had given up any hope of convincing anybody I was right. I was in it for the love of the game…which is why I was dangerous.

Anyway, this already bad situation was made much worse by the various B.C.O.’s irritating habit of slapping “PARODY” on any book they thought might attract negative attention. This has led to the term “parody” becoming completely meaningless within book publishing. As I type, Amazon’s best-selling book in the “Parody” section is The Screaming Goat (Book & Figure) which is touted as a way for “goat and animal lovers to celebrate their favorite internet sensation with a hilarious, one-of-a-kind screaming goat!”

You can imagine what happened when I showed up with—no, not a screaming goat figurine, but a first chapter of a close parody of Harry Potter. People acted as though I’d given them a turd in a box. Which was particularly galling because I had only written it at the request of an editor at St. Martin’s. Who loved it, showed it to his acquisition committee and…turd-in-a-box.

All big New York houses, all turd-in-a-box. “But wait,” you say, “didn’t you have an agent?” Yes, my first agent. This one agreed to take the manuscript around to some editors—in exchange for 15% of all sales, irrevocable, in all formats, forever, until the Sun explodes; you know, apparently the standard deal—but couldn’t sell it. When he gave it back to me, he rather defiantly explained he was glad it hadn’t sold because he thought “books like that should be illegal.”

“You mean, parodies of the most successful children’s book of all time? Which you couldn’t sell?”

“Right!” I don’t think he got the joke.

• • •

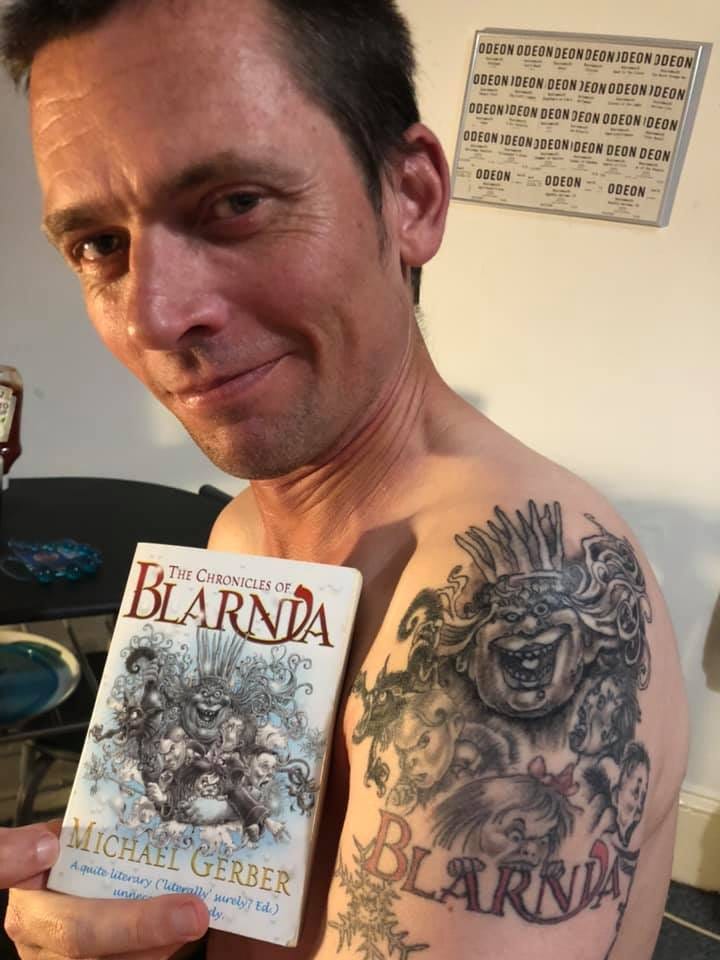

So I self-published Barry, and when it didn’t get sued—JKR reportedly liked it; she gave it shout-outs in the next three Harry Potter books—I had a good little 25-language hustle going for a while. Sure, my UK publisher had an irritating habit of asking me to do sequels in six weeks—”C’mon, Mike, it’s only jokes”—but I was not complaining. For two years I got paid like a mid-tier lawyer, which was awesome. I loved interacting with fans, and still have a bunch of letters I received. One reader loved my Narnia parody so much, he got a tattoo of the cover.

Publishing sucks, really it does, but this photo makes it all worth it. Eternal hat-tip to you, D.C.

After four or five parody novels, I was eager for a new challenge, so I began writing a roman a clef about a kid from the Midwest who goes to an impossibly wealthy, impossibly fancy Ivy League school. Going to Yale was, for me, a psychedelic experience, beginning the day I got accepted and…my parents treated me different. Deal with that for a second—my parents treated me different. “Shit, we thought you were just a weird loser, but now…” Girls suddenly got interested in me, I started getting invitations to parties. I was the same ol’ guy, but with that brand name attached, suddenly I was Going Places.

Of course, I’d been Going Places since I was three, when I realized that the alternative was Going Noplace. That was absolutely intolerable; we were living in my grandmother’s house in Ballwin, Missouri and—I loved my grandma, but getmeouttahere.

My mom felt the same way. When I was three, we were in her beat up VW bug—the one we called “the Claes Oldenburg car” (it had melted radio buttons from an ashtray fire)—when we pulled up behind a car with a Harvard sticker on the back window.

“Someday you’ll go to a place like that, Michael,” my mother said.

“Can you come too?” I replied.

That’s the family story anyway.

• • •

So FRESHMAN is about all that, the weirdness of the whole Ivy thing, and about my personal experience at Yale (which does not have any vampires that I know of) and on The Yale Record humor magazine (which, if any place at Yale could have vampires, would). Speaking of, I’ll be going back to New Haven in April to celebrate the 150th anniversary of The Record, and just today I got wind that they’re going to try to rope me into giving a few informal talks. If there’s interest, I’ll see if I can livestream ’em here.

I hope I can hold up physically through that—I’m strong as an ox, but as I type this at 2:03 A.M., I feel it’s quite a strain to do The Bystander; then there’s travel; and I can never stop myself from giving my all when there’s an audience of students willing to learn. That youthful crusader still lives, I guess. I fully expect to have both talks end like a James Brown concert; someone comes up onstage with a cape, and leads my crumpled, sweaty form offstage as the band plays on…

Very nice. Informative, meandering, and bitter. In a good way. Perhaps what is needed is a parody about an embittered humor writer? Who cares what I think?

Appreciated this. At once informative, enjoyable, and terrifying (from a publication perspective in 2023). When the odds are stacked so much against writers, where will great literature and longform humor (which can be great literature) emerge? Maybe from remote corners of the world where people are doing it for the love of it, appearing circumstantially decades later, or in hoity-toity places where literature is still kind of supported, like, you know, France.