Weasel Question Time #1

Young Pershan asks, "Wait—you sat in editorial meetings at National Lampoon?"

Indeed I did! That came at the end of more than 15 years of thinking about Lampoon, which I probably shouldn’t have been thinking about at all. I was born in 1969—The Onion is my generation’s magazine, with original writers all around my age. But all print humor since 1970 is in conversation with The National Lampoon—The Onion, SPY, of course Bystander itself.

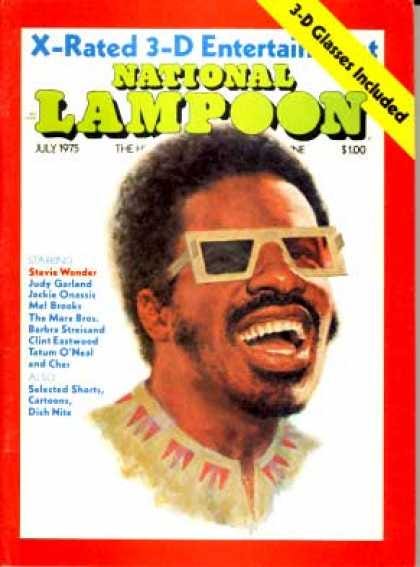

My mother had a Lampoon subscription when I was a boy—I remember this issue, because we were a Stevie-worshipping household, and this is an excellently art-directed cover. But Mom hid her issues when she discovered I was getting the sex jokes. This of course was part of the appeal—like Alvy Singer in Annie Hall, I didn’t have much of a latency period—but Lampoon’s hold on me was also rooted in how it constantly referenced Boomer history and culture. I grew up with a strong sense that something quite great and important had happened, but I’d just missed it.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The American Bystander's Viral Load to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.