BY MICHAEL GERBER • Last Friday I learned from Bystander Steve Brodner’s

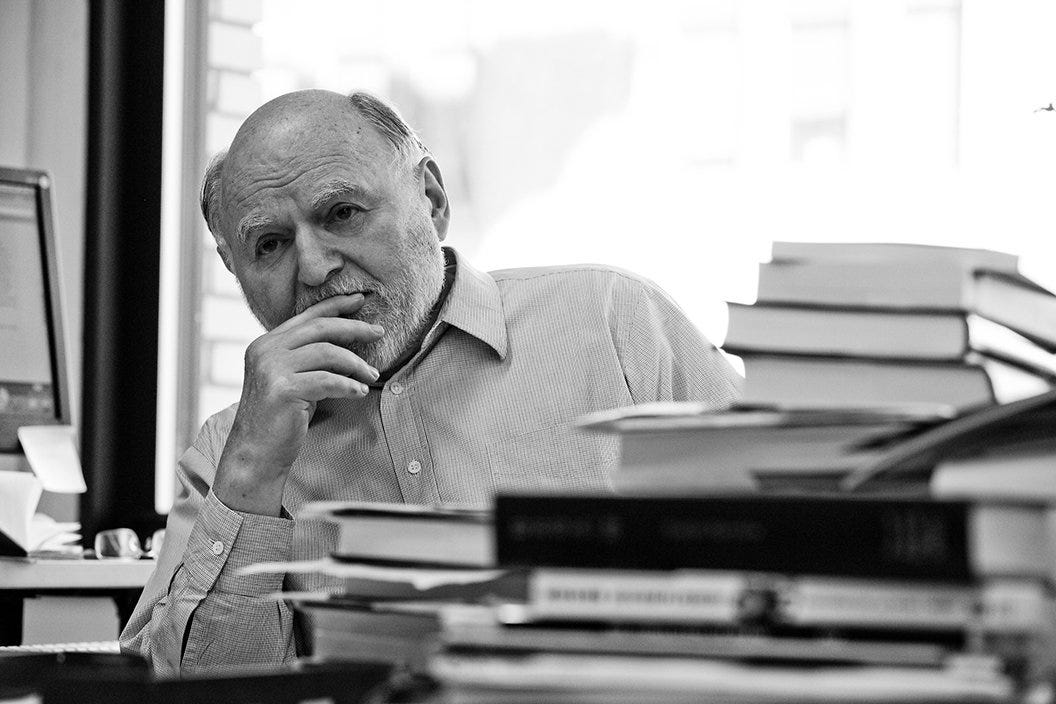

that a minor giant had passed away, Victor Navasky.Don’t misunderstand, Vic was as big as they get; to paraphrase Norma Desmond, it was publishing that got small.

I first met Vic around 1999, to interview him for a history of comedy I was writing for St. Martin’s. That soufflé never rose, but I remember spending a happy hour with him, listening to stories. “Oh sure, I met Peter Cook and Dudley Moore. I went up to their hotel suite when Beyond the Fringe was on Broadway, 1963 or ’64. Peter opened the door and my mouth just dropped. I saw that all the furniture had been cleared out, and he’d put up this immense tent. There were pillows all over the floor, which Dudley and the rest were sitting on, including several of the most beautiful women I’d ever seen. I thought, ‘I’m in the wrong business.’”

Vic’s business was to embody liberalism in print. He wrote books. He taught. And he ran magazines. As first the Editor and later the Publisher of The Nation, he was immortalized by Calvin Trillin as “the wily and parsimonious Victor S. Navasky,” a phrase so funny that I aspire to it, both as a writer and a publisher.

My hat is off to Vic for lots of reasons, but it takes a truly unique person to be both an Editor and a Publisher. The mindsets are simply very different, one side usually gets short shrift, and that side is the money. (Ask me how I know.) Editing The Nation would require a mind of rare sharpness and stamina, but publishing it? I don’t know how anybody could pull that off. Asking rich people to back The Nation would be like asking the Vatican to fund Pederasty Today. But Vic did it, somehow. Not coincidentally, the man raised $75,000 1963 dollars to publish a humor magazine. That’s roughly $727,500 in today’s money. If you gave me a check for $727,500, Bystander could publish for the next 4,000 years.

But did I ever call up Vic? Did I ever try and wheedle away his publishing secrets? Of course not. Because I’m an Editor, no matter how many hats I wear.

In 1957, when Vic was still at Yale Law School, he gathered a group of funny friends and started a satirical magazine called Monocle. According to an article in TIME written seven years later, “The first issue sold briskly on campus, encouraging the fledgling editor to abandon the law and move to New York.”

Monocle was a product of the satire boom of the late ’50s and early ’60s, making its debut around the same time as The Second City, a slew of nightclub comics we still revere, and Paul Krassner’s The Realist. Monocle was, broadly speaking, Mort Sahl to The Realist’s Lenny Bruce; more measured, less manic, a head-first kind of humor. Monocle might smoke a joint, but was scared to drop acid—they might freak out and forget to vote.

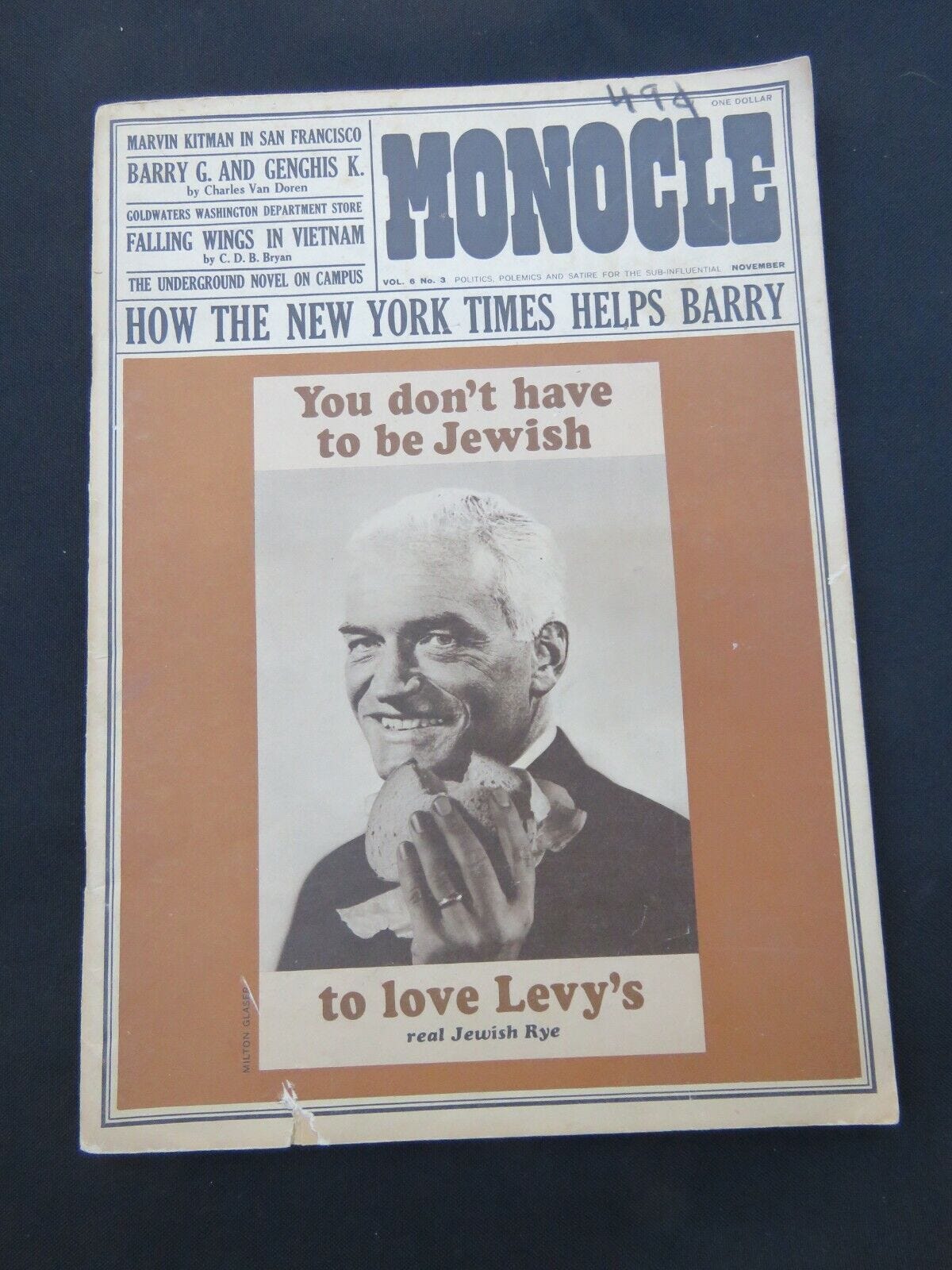

Monocle also looked great, especially the typography. Just like the material was an important way station between MAD and The National Lampoon, Monocle’s graphic style surfaced a lot of things that would later become omnipresent in the graphic language of the counterculture. Many of the artists behind The Push Pin Graphic, for example, people like Ed Sorel, Seymour Chwast and James McMullan, were featured in Monocle. (Not coincidentally, all three are in Bystander.) Once you know Monocle’s look and contributors’ list, you see it everywhere, from Esquire to The East Village Other. Graphic designer and historian Steven Heller wrote this affectionate appreciation of Monocle in 2009. Steve being the genius he is, I cannot improve upon one word. It’s only archived on the Internet Wayback Machine, so read it while you can.

Monocle survived for seven and a half years—precisely the same age Bystander is now [creepy sting]—doing great work but unable to make the shift from the era of the button-down mind to the chemically blown one. It didn’t really need to; Monocle’s mark had been made.

It’s interesting to note that The Realist’s biggest splash, “The Parts That Were Left Out of the Kennedy Book,” a shocking and sexual spoof involving William Manchester’s then-new Death of a President, was published in May 1967, just after Monocle had shuttered for good. It wasn’t just that Bystander Krassner’s one-man, scandal-savvy, agitprop newsletter was a more durable model for the era of the head shop, it was also that satire was shooting off into darker, more explicit areas, places Monocle wouldn’t go.

But that didn’t mean Monocle’s approach didn’t also make its mark. In November, 1967, Vic and several other Monocle writers helped birth Report from Iron Mountain, a bogus government report written by Leonard Lewin. Lewin’s book was so tongue-in-cheek that most took Iron Mountain to be an authentic government report. (“Whoever wrote it is an idiot,” Henry Kissinger said, feeling the satire strike a little too close to home.) While some people believed Krassner’s article (most notably Daniel Ellsberg), Iron Mountain’s parentage is debated even today, even after Lewin outed himself in The New York Review of Books.

Monocle never broke big like Lampoon, but it was never intended to do so; like The Realist, it defined satire as a sport of the few. For satire to be a mass taste, the (Iron) mountain would have to come to Mohammad…which it eventually did. But by that time, all the Monocleers had moved on. They had kids, jobs, mortgages. Monocle was satire of the Establishment for people inside the Establishment, by people who could’ve lived that life but said no. They could write like governmental officials because, in an earlier era, they would’ve been government officials.

I have a collection of old humor magazines, purchased from eBay; I keep them as totems, markers of my respect, a connection to editors I admire. My copy of Monocle is from November 1964; the cover spoofs the old Levy’s Rye Bread ad campaign, with candidate Barry Goldwater smiling from behind a sandwich. (That campaign was the brainchild of George Lois, who died last November. All the old lions are going.)

Like a lot of things in my life, this gesture does not come without cost; old magazines are treacherous to me. In the depths of my immune system disorder I developed a severe allergy to book dust, and after only a few minutes of reading, I am wheezing, my eyes are red, and my fingertips burn. It is a drag—and quite a blow to a man who had until then spent his happiest hours in used bookstores and research libraries. But will I throw this magazine away? NEVER. I have a special place in my heart for Monocle, not just because of Vic, who was kind to me and so funny and smart, but because it flowed from the high point of my old college rag, The Yale Record.

When Vic hit campus in 1956, something really special was going on in New Haven. From 1947-62, The Record boasted a run of student cartoonists unequaled in the history of college humor magazines; several of these, like James Stevenson and William Hamilton, set the tone for The New Yorker for the next fifty years. Others, like Robert Grossman, blazed trails in illustration. A few like William Cuhady, fell victim to misfortune before fulfilling their early promise; and Bystander’s own Don Watson is finally doing so after a many-decade sojourn inside the Establishment. But as a group they were remarkable; the only outfit that came close was, perhaps, The Texas Ranger in the days of Gilbert Shelton.

Vic was at YLS the same year our pal C.D.B. Bryan was Chairman of The Record. I’m sure I’ll write more about Courty here—he was a wonderful, outsized character with a kaleidoscopic brain. C.D.B. assumed the Editor’s chair at Monocle after a few unhappy years in Army intelligence; and while at Monocle was already writing about Vietnam. He would later write the book Friendly Fire.

To my eye, The Yale Record and Monocle have the same relationship, more or less, that The Harvard Lampoon did with The National Lampoon ten years later. As ever, the Harvards have a better sense of timing, but let’s pour one out for our homies. Witty rather than broad, artistic rather than shocking, The Record and Monocle practiced a type of print humor magazine that bubbles up every so often, when the culture seems to need to take a breath; I’d put the early New Yorker in this bucket, too. It’s maybe not the most popular style—jazz in a world that prefers rock—but an important one. It’s the one The American Bystander uses today, and I would not be at all surprised if there comes another magazine that takes what we’re doing now, sexes it up, and sells it to the masses. Maybe we should cut out the middleman and do it ourselves? Add a centerfold and call it Bystander Blue.

Monocle disappeared before the Sixties got really ugly. That’s probably why it disappeared; 1968 was not a time for Apollonian satire. Navasky’s humor magazine balanced irreverence with a sense that American culture was good and redeemable, that Americans were intelligent and fair-minded, and that society was—with lots of mistakes along the way—on the right track. Like Lenny Bruce, Monocle believed in America, even when there was little reason to do so. Monocle sought to convince a country it considered fundamentally decent and sane the error of its ways. It tried, through laughter, to weld people together—to show anybody alarmed or appalled that others were alarmed and appalled as well. It was funny but also intelligent, humane, human.

For all that, I admired Monocle. And I admired Vic for it, too.

That last full paragraph is one of the finest you’ve ever written. Bonus points for working in “Apollonian satire”, but a genuinely heartfelt and important point to make, perhaps now more than ever. It is not unhip to believe in their country, in its people, in the power of humor and reason, in that essential faith that William James spoke of, that Ralph Waldo Emerson embraced, that James Baldwin illuminated... ours is a complicated history, and the present moment can seem overwhelmingly depressing, but mebbe smart humor may help light the path outta this fucking mess.

Another fascinating piece of comedy history I never would’ve known about otherwise. Thank you, Michael!

I would also consider, in neon purple cursive, Bystander NIGHTS.