Okay, first the boring part, to bring everybody up to speed.

On November 28, The Atlantic published an article called “Substack Has a Nazi Problem,” wherein writer Jonathan Katz turned over some rather wormy rocks. “An informal search of the Substack website and of extremist Telegram channels that circulate Substack posts,” Katz wrote, “turns up scores of white-supremacist, neo-Confederate, and explicitly Nazi newsletters on Substack—many of them apparently started in the past year.”

Part of what makes our contemporary pas-de-deux with Fascism so infuriating is we already know everything about it. We know what they do, how they lie, who believes it, who gets killed, and how the story ends with everyone, Fascist or not, either dead or living under rocks. Fascism always embraces tech to spread its ideology; just as Mussolini and Hitler used radio and movies, today’s Fascists will use social media, Substack, and whatever else, including dildonics if they can figure out how. And the grip of that tech-driven fantasy is so strong, mere reality cannot compete; as IRL Russians surrounded the IRL Führerbunker, Goebbels was still pushing his “wonder weapons” meme.

Substack has a zero-tolerance policy towards some things—they won’t platform sex workers or anything else they deem porn, for example—but political bad actors, apparently, they’re willing to give the benefit of the doubt. Responding to a group of anti-Nazi Substackers who wrote an open letter, Substack co-founder Hamish McKenzie replied in this Note, “We believe that supporting individual rights and civil liberties while subjecting ideas to open discourse is the best way to strip bad ideas of their power. We are committed to upholding and protecting freedom of expression, even when it hurts.”

“…other people,” I’m tempted to add. Because from a short-term business perspective platforming Nazis doesn’t hurt Substack—unlike Twitter, there are no advertisers to cancel their ad buys. And one of the sacraments of modern Tech is that, unlike every publisher before them, digital outfits can somehow “publish” things without being responsible for them. In the eyes of the STEM folks who create the apps and the flacks who run interference, the code-only nature of digital platforms render them neutral somehow, uninvolved. Twitter or Facebook or Substack, they are simply providing an arena where the “best ideas” can fight their way to the top, and the techies make a clean dollar by charging the spectators admission.

That’s not how any of this works, and if we didn’t know it in 2005, we sure as shit do now. To publish—on paper or via cable or pixels—is to vouch for, and spread, and allow to spread, and Nazi ideas have been thoroughly tried and tested and found to be destructive and evil. Nazi ideas get your audience killed. Every publisher knows this; it’s just that some publishers cynically think it won’t be their readers.

Every publisher publishes things that, on retrospect, were unwise; the hard calls are part of the job. Nazi stuff isn’t a hard call. There’s only one right thing to do here, it’s obvious, and either Substack is going to nut up and do it, or this whole pullulating lump of ones and zeros is going to become Inbox Twitter.

Time to scrub the site, you guys. But I feel for you, and here’s why.

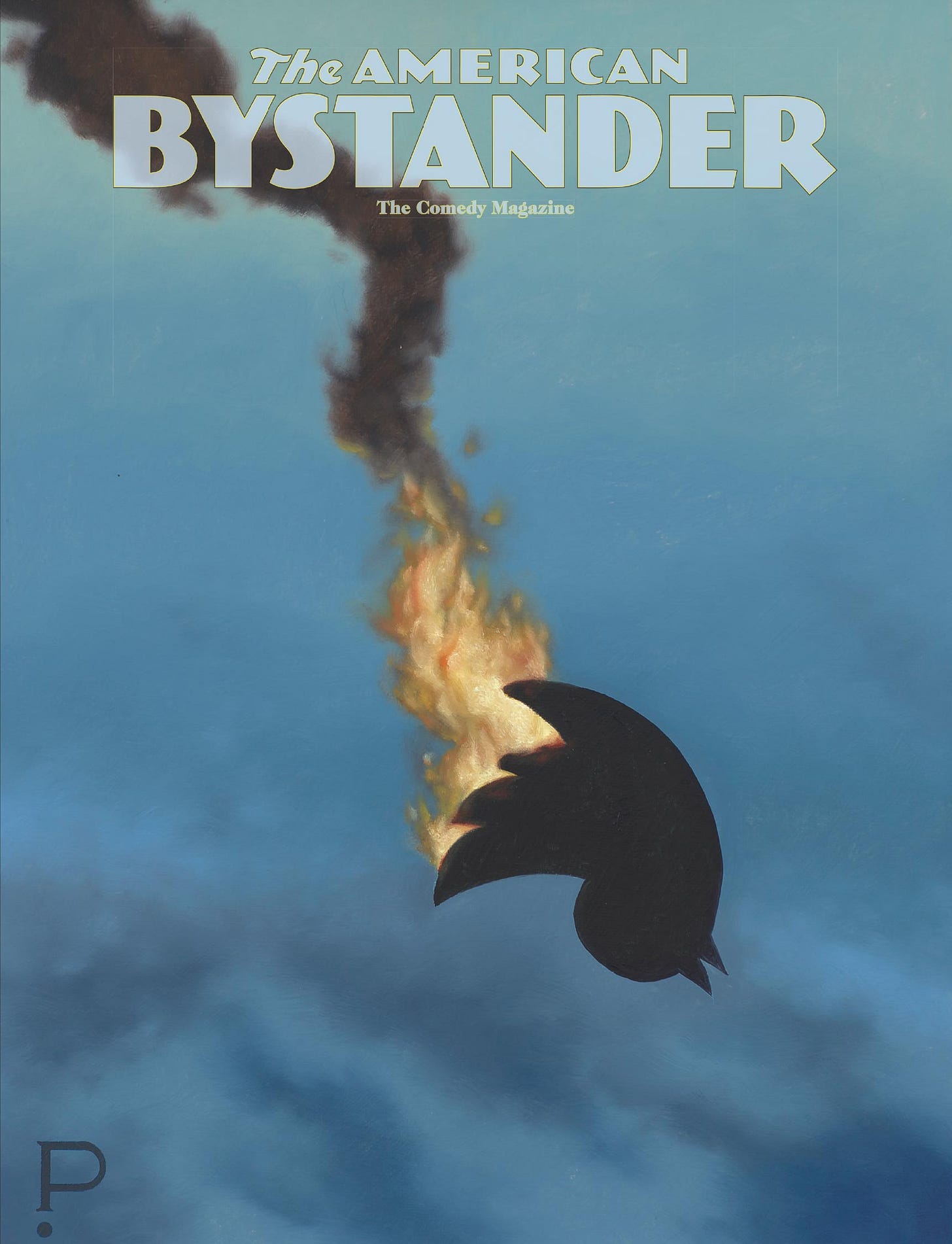

In 2015, when I resurrected Brian McConnachie’s almost-published print humor magazine from 1981 called The American Bystander, I felt like a circus performer standing on two horses. The goal was to get as far as possible before the horses ran away from each other, and I looked like a total idiot and also broke every bone in my body.

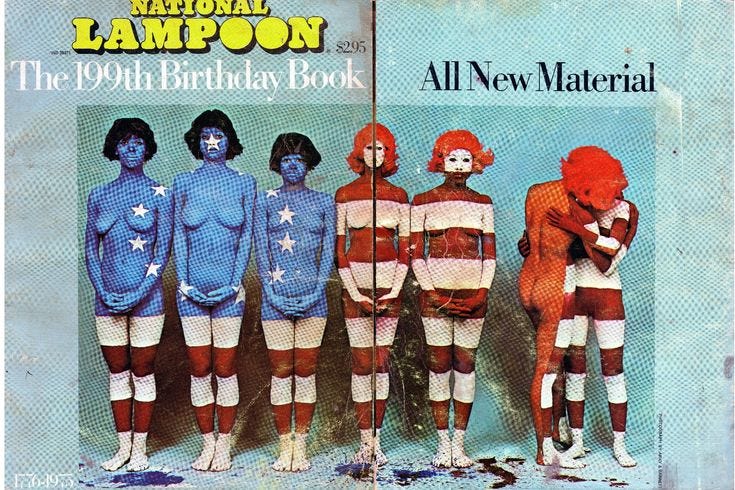

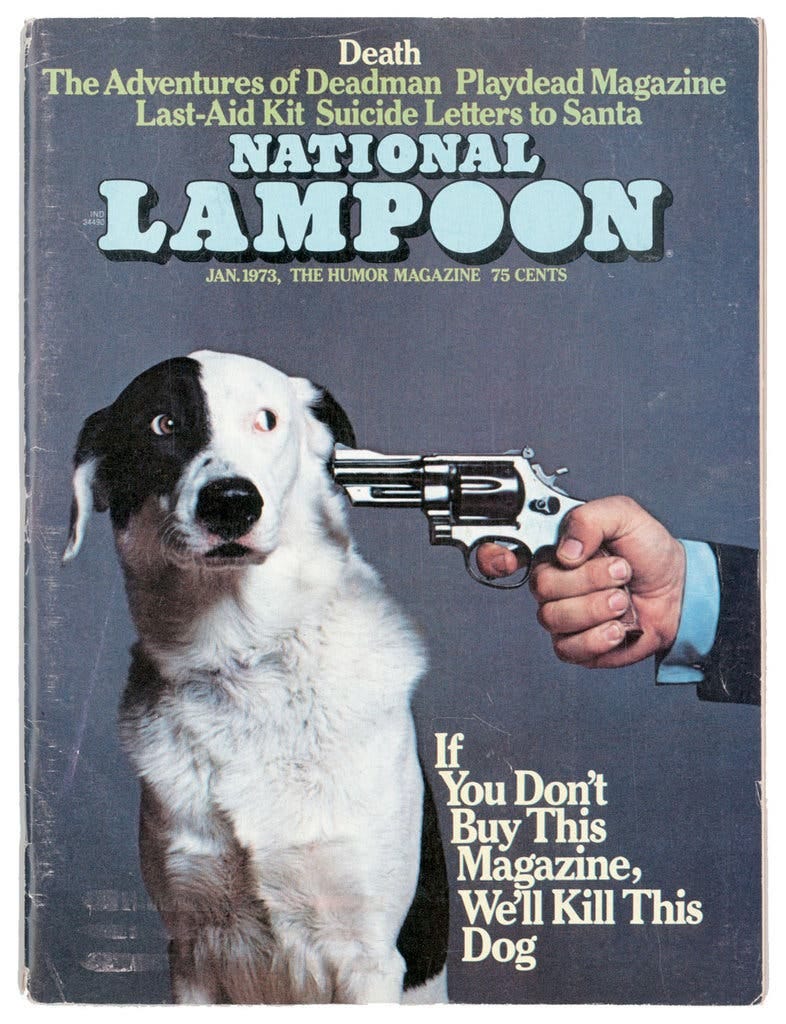

The first horse was our pitch: we were offering a magazine that featured a lot of people from the dear, departed National Lampoon. If you’re under 50, you really can’t understand what powerful juju this was. Most comedy-heads know that Lampoon helped define modern comedy. But if you were a (white, male) kid between the years 1970-85 or so, The National Lampoon acted less like a print humor magazine and more like a powerful psychotropic. In addition to being very funny—your own secret South Park or Rick and Morty—Lampoon was often the first place you saw tits or pubic hair. This made it primally thrilling; Lampoon offered sexual content in an era where that was strictly regulated and unimaginably rare. Unfortunately, by the 1980s, its institutional mandate to be outrageous had also moved it into some pretty extreme racism and sexism…but readers, especially the younger ones, went along with it. Lampoon’s writing was good, the illustrations were funny, but the snap and sparkle arose from the fact that we all knew—the writers, the illustrators, and especially the readers—that every page would upset Mom. That made the jokes a lot better; that was the Secret Sauce. When you read Lampoon you weren’t a reader—you were a member of a secret club of free men. Honest, devoted to Truth, unafraid of Mom.

How much of MAGA is white men from precisely this era—Boomers and Gen X—who define freedom as precisely the feeling they got from reading National Lampoon at age 14? How many people hated Hillary Clinton precisely because she was Mom?

And I get it. I’m 54. As a person ages, that sense of who-gives-a-fuck becomes ever-rarer, until it looms like Gatsby’s green light. So…a new magazine full of the writers and artists who used to give me that sweet who-gives-a-fuck? Sign me up! I got many emails from comedy notables, expressing excitement and support, and every single one of them mentioned this sense of freedom via outrageousness, how it was so powerful they still remembered it, how it determined their career, how much they missed it, how much they longed for it. And if some star making $10 million a year still feels hemmed in by Mom—not his Mom, she’s probably dead, but the Over-Mom—imagine the craving of some guy in Chillicothe, finishing out a drab career in IT.

Brothers and sisters, my path to million$ lay open.

But there was a second horse, which is our current media environment. In two clicks, any person can be dick-deep in hardcore sex of any type, or outrageous politics, or outlandish conspiracies. (To test this theory, I just typed in “John Wayne Gacy slash fiction” and sure enough, there’s a section on Archive of Our Own. I didn’t click through.) What would Bystander have to publish to provide that same yawp of anti-Mom buzz Lampoon delivered in 1974? Today, a person in the editor’s chair wouldn’t simply have to have a free-and-easy attitude towards bush and BDSM, but a total lack of responsibility towards what they were putting into the world. They couldn’t care what type of readers they were serving—what type of people they were creating. Because the boundaries of outrageousness have been pushed out so far, I couldn’t preside over “a new National Lampoon” without becoming a monster myself, working with a bunch of monsters, and also creating a bunch of monsters for everyone else to deal with.

My solution to this two-horse problem has been roughly the same as Substack’s—a lot of first-person stuff. It’s your story, you defend it. But because those old Lampoon writers were 65 and not 25, wracked with ED and Peyronie’s Disease, and it was 2015 and not 1973, it was all very low-key stuff. Frequently funny—but there was no anti-Mom; no “I-can’t-believe-they-published-that!”

The famous people all unsubscribed by issue #3.

Contemporary comedy is a lot like contemporary political speech; because of vast, vast oversupply, the only economic advantage is to be found on the fringes. In a world where a handful of mega-corporations own the mainstream, for independent producers—be it the right-wing standups so ably chronicled by Seth Simons, or “dirtbag left” podcasts like Chapo Trap House—there have been big monetary rewards for wrapping a pretty standard kind of satire in fringe political points of view. Those are the audiences longing to be welded together. Sometimes there doesn’t even have to be much comedy there; does anybody really think that The Babylon Bee persists because of an unmet need for parody news?

The election of Trump in 2016 made my two-horse dance impossible; I had to let outrage go entirely, and leap to decency. The moment civility cracked and that man waddled through, the stakes were clearly too high to fuck around. I toyed with the idea of going “blue”—letting sex provide the outrage—and I still might, but that too has a ceiling on it. For one thing, places like Substack won’t allow it; the corporate mainstream may be okay with Day One Dictators, but exposed pudenda are definitely not acceptable. (For reasons, I must admit, I do not fathom.)

But I don’t even need sex; were I in this solely to make a buck, it would be the easiest thing imaginable to turn The American Bystander from a mainstream humor magazine into a Buckley-ite peering-down-the-nose “satire” rag. It’s a genteel-looking print magazine; I’m a Yale guy who cleans up pretty good and will talk your ear off about Ancient Rome—think Lewis Lapham, only half as tall and twice as dirty. Shit, The American Bystander already sounds like the Cato Institute’s in-house dating Discord.

Two hours after publicly pivoting right, I’d have three or four deep-pocketed reactionaries knocking on my door, looking to invest. I even know their names. The one thing the right-wing has never been able to buy is laughter; from Elon on down, it burns them that as rich and powerful as they get, nobody thinks they’re funny. Part of this is immaturity, but they also know how useful comedy can be. Comedians like to talk about how jokes bring us together—“shared humanity argyle-bargle”—but jokes are actually even better at defining who’s human and who’s not. Jim Crow thrived on racial humor, and when the Nazis were in charge of UfA, they made more comedies than any other type of movie.

So I get it, Substack. I get there’s money to be made in Nazis and other horrible freaks desperate for validation and community. They’re mad at the Over-Mom and aching for media that reflects and amplifies their twisted world views, opinions that we know lead to nothing but Auschwitz for some, and Dresden for the rest. I get that it’s really tempting to pretend that there’s some big difference between Bill’s Replacement Theory Book Club and Der Stürmer, and that there will be some obvious moment where you can deplatform Bill because he’s finally gone too far. Most of all, I get that it’s difficult and thankless to do the grown-up thing, and drop this fantasy that because it’s all digital and not dead trees, you can be blissfully uninvolved, that Substack is just Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park, and you’re just collecting donations and taking a cut.

But it ain’t so. You’re a publisher, just like me, and to be a publisher isn’t just to make money from content; it’s having your own personal morality and vision of the world expressed, however imperfectly, by what you publish. You know this, Substack—you are against sex work and sexually explicit content, so you don’t publish it. I disagree strongly with this decision—in part because I grew up in the 1970s, where sex was okay but Christofascism was not, and in part because I see it as unfairly restricting some of society’s most disadvantaged, most ostracized people from making a living. But I accept it as Substack being a PUBLISHER.

What you publish is who you are, and I say that as someone with a pile of stuff that—were I important, which I am not—someone could go through and present me with a Document of Shame containing all the things I’ve written that I shouldn’t have, that looking back now, I wish I hadn’t and would certainly feel bad about. Jokes at people’s expense, things that weren’t fair or well thought-out or maybe made some kid in 2003 feel bad. I’d hate that, and after 35 years of doing this professionally, there’s doubtless a pile of it.

But that’s not the measure of a publisher—it’s what you do next that matters.

So do the right thing, guys. Boot the Nazis. And to everybody reading this: Season’s Greetin’s. I wish each of you warmth and happiness on this, the darkest day of the year.

"Move fast and break things" was Zuckerberg's motto. Obvious result: a lot of broken shit and tech bros fleeing to Turks & Caicos with their lucre.

We need to force the Nazis and neo-confederates off this site so they need to build their own platform. Save the FBI some monitoring time.

My values lean heavily in the direction of free speech as a matter of cultural norms and not just legal principle, but I'm with you on this one Mike - that doesn't extend to Nazis on Substack. And here "Nazis" doesn't mean "everyone right of centre", it clearly means "people proudly displaying swastikas who stoke fears about coordinated plots to overthrow white people".

When people talk about airing all views so that the best ones can win, that ignores the fact that Substack isn't a campus, it's a newsletter site where people naturally gather into silos. Lefty Substack publications aren't "debating" Nazi ones, and even if they were I doubt they'd do much good. (Hearts and minds can be changed, yes, sometimes, but in the case of deep-seated bigotry the changing entails lots and lots of in-depth in-person interactions, not a snappy comeback on an Internet forum. People's worldviews derive more from their personalities and needs than dispassionate logic, and always will.)

So here you have a situation where Nazi propaganda, far from being aired and debated in an open forum, is being piped directly into the inboxes of people who are already open to it. It's not even Hyde Park, it's an exclusive book club. Which results in a genuine online community, which results in better organising, which results in more in-person gatherings, which...well, let's just kick 'em out.