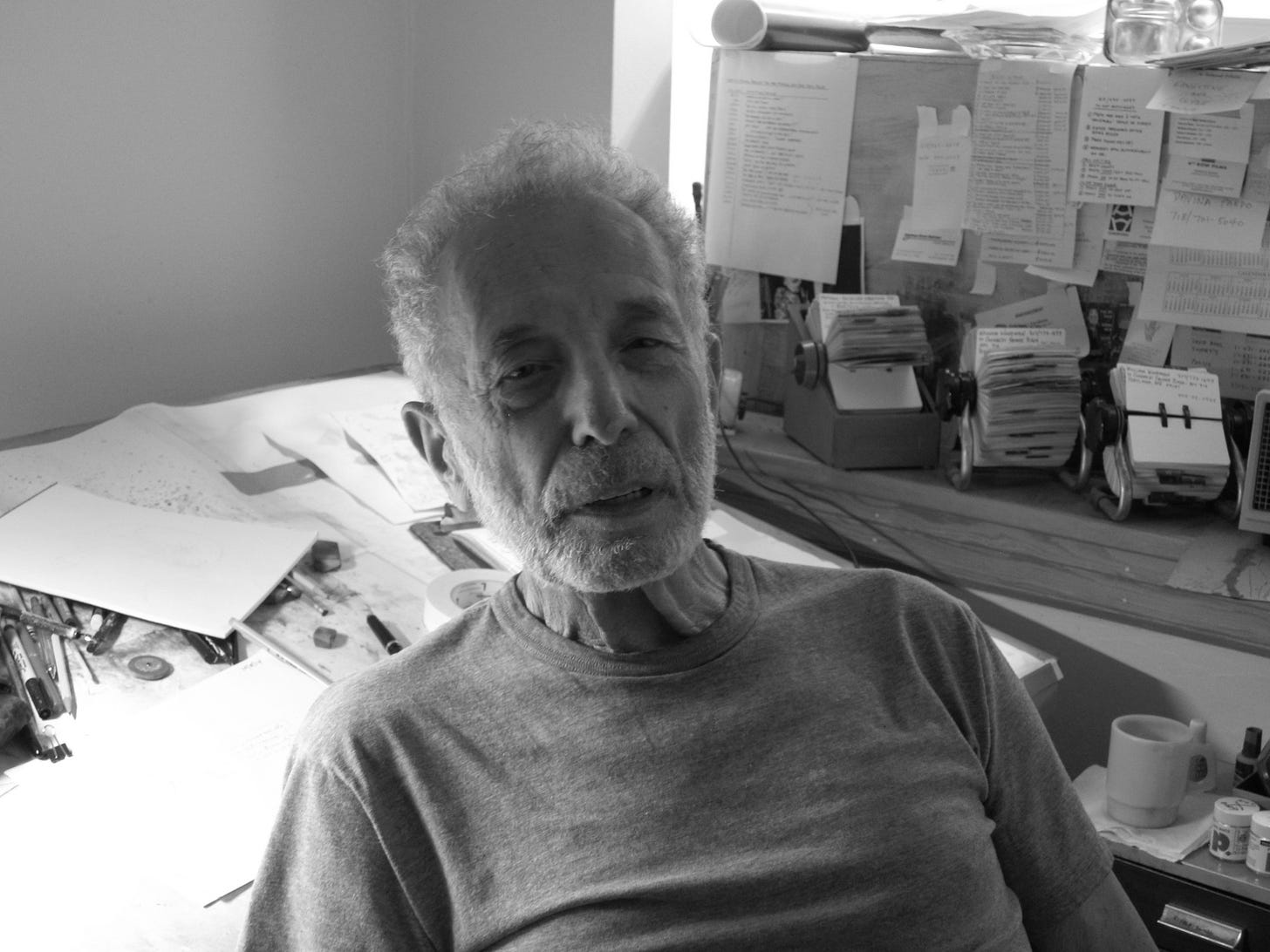

The cartoonist Sam Gross died last Saturday, after a long illness. “It’s called ‘old-as-fuckitis.’”

I’ve been hearing Sam’s voice in my head a lot since I got the news. When I called his wife Isabelle and their daughter Michelle early Sunday to sniffle and mouth platitudes, the ladies were very kind.

Sam, on the other hand, gave me shit.

MG: “Is there anything I can do?”

Bring back my husband, asshole!

Isabelle: “You’re doing it right now. Thank you.”

Misha: “Thanks for calling, Michael. Just know Sam loved you.”

With your rates, I sure as shit wasn’t doing it for the money!

Ghost Sam’s abuse made things easier, somehow. Sam’s customary greeting to me was, “Your magazine looks like shit,” and it took a couple of issues to realize that meant, “I’m proud of you. Keep up the good work. I’m about to teach you something useful.” Sam advised me from before the first issue, and while I never actually called him our Cartoon Editor—I didn’t want him to be embarrassed if I fucked up Brian’s baby and we failed—Sam was constantly in there, advising me, encouraging me, and telling me how to make Bystander better. I hung on every word—when it came to cartooning, Sam Gross knew. Any mistakes are totally my own; to whatever degree we do cartoons well, that’s all due to what Sam taught.

As we talked, Isabelle reeled off a long list of maladies that Sam had been fighting, privately, for a long time, including ones that were slowly destroying his ability to draw. God, I thought, if You exist, you are one cruel asshole.

This wasn’t news to Sam Gross.

I’m no scholar of cartooning—lots of those exist now, thanks in part to Sam’s championing of the art—but in my rough-and-ready estimation, if you look at the people our society holds up as the great one-panel artists—Thurber, for example, or Charles Addams—these fellows all had a big institution around them, mecha-like, reflecting glory upon them for its own purposes. As much as I enjoy his work, the ongoing Thurber Cult is mostly a function of The New Yorker’s PR Department, and if that magazine had died with Ross in 1951, Thurber would be as relevant today as the rest of the Round Table. This is no blot on his reputation; even a talent as unique and powerful as Gahan Wilson needed Hefner’s vast Imperium Playborium to provide the proper stage and context.

Sam Gross was different. Wherever he appeared, from Good Housekeeping to The National Lampoon to The American Bystander, he was indisputably, undeniably himself. Sam was very easy to edit—you didn’t—because like light pouring into a black hole, he bent the magazine around him. His talent was so great, his world and worldview so hilarious, that Sam Gross didn’t need the context of an institution. He was, and remained to the very end, too big for that. You did not publish Sam Gross; he allowed you to print a small sliver of his reality, and you were grateful.

Now that’s gone, and there won’t be another like him. Why? Because Sam Gross was a great, great talent, formed by a unique time in American culture. When he died a person died, for sure, but also a whole era, a set of lived experiences as gone as the saber-toothed tiger. When you were in the presence of Sam Gross, you felt all that had conspired to make him, from fairy stories to fist-fucking, to the days when books and magazines—and thus, cartoonists—could really work and earn and develop and thrive.

• • •

Sam Gross came up in the time of the so-called “Sick Comic,” and I believe that he was to gag cartooning basically what Lenny Bruce was to standup. But working was Sam’s drug of choice, so rather than being a martyr, Sam was a mentor; a colleague; an advocate; a mensch. Sam did not mythologize himself; he just did the work. Sam’s longtime right hand Patrick Giles—in addition to his other hand, his daughter Michelle—told me yesterday that Sam had 30,600 cartoons in his archive, all neatly numbered and filed in binders. Cartooning was his vice, and he lived and drew, until his body gave out. Those last weeks, not being able to realize the ideas in his head must’ve been pure torture for him, something dark enough for a Gross cartoon. Many people have marveled at Sam’s productivity, chalking it up to an ex-accountant’s work habits, but I think after his midlife heart attack he was on a clock, doing everything he could before time ran out. Imagine staring Death in the face and growling, “Fuck you.” Sam had a job to do, and he wasn’t going to let a mere myocardial infarction stand in his way.

By the end, I think he was staying around for us, probably since Trump got elected—but at 2:22 p.m. on May 6, he’d finally had enough. “Fuck it. If you people haven’t gotten it by now, there’s no help for you.”

So what did Sam want us to get? He never told me, but I have some guesses.

• • •

The Owners of America have always hated and feared our artists, and made things as difficult as possible for them. Sam felt this in his bones, and hated the Owners right back. He conducted his business in the bareknuckled way required to win. (Except when he didn’t; my rates are currently a matter for Amnesty International, but we’re trying to fix that.) Sam never had any illusions about media corporations, or the armies of suck-ups and apologists in their employ. Religious groups were seen, appropriately, as just another hierarchy, another manipulating, repressive, inhuman authority.

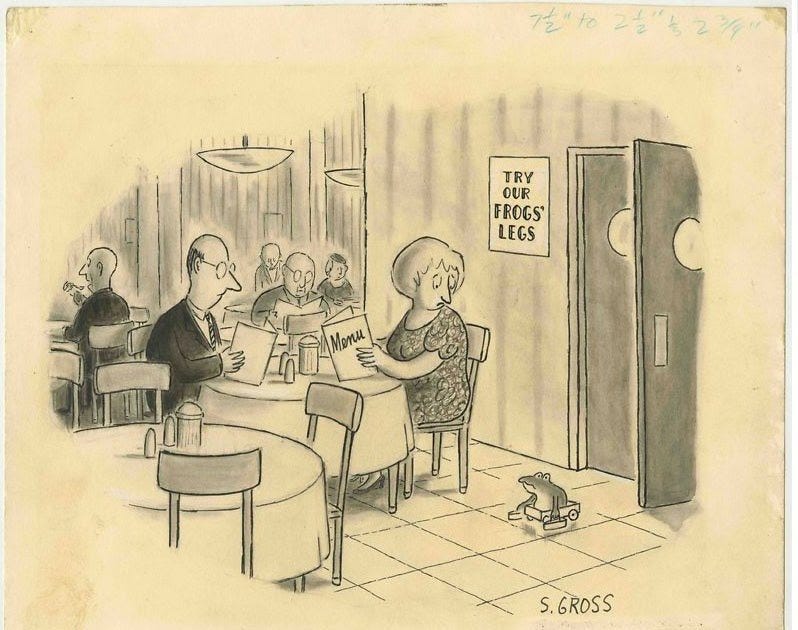

Like the other great “sick” comedians that came of age in the late 50s and early 60s, Sam used taboo as fuel, but behind the shock there was a hard reality. Your fancy dinner is someone else’s legs. Sam’s genius was a kind of radical honesty, which led him to places others would not go.

His deceptively simple style—almost sweet—was the perfect delivery system for these dark realities, which included the fundamental strangeness and absurdity of having a body, and the crazy nonsense it makes us all do. Piss, shit, come, blood—this was Sam’s beat, and as soon as the culture allowed him to speak openly about it in public, he did so. At length.

Like the best artists of his generation, Sam Gross believed fiercely in the rights of the individual—but Modern American life has no room for individuals. Even supposed lone geniuses like Steve Jobs are in reality just another asshole at the top of an org chart. For the 0.01% to make all the money they require, there must be no loopholes, no free space for the rest of us; we must all be in harness. Sam fucking hated that, and rightly so. He fucking hated the internet, and especially fucking hated social media. “Exposure?” he’d say. “That’s something you can die from.”

Sam never fit into the world wide web, this land of supposed freedom where supposedly rational people “just ask questions” about eugenics but the cheerfully, harmlessly DTF have to use absurd workarounds like “seggs” just to outwit the algo. Sam lived in the realm of the Id, but he remained absolutely crystal-clear on right and wrong, and that’ll get you dinged in cyberspace. Sam was often accused of bad taste, but I’ll take his moral compass over Facebook’s, or CNN’s, or SNL’s. In Samworld, sex is okay, shit is okay, kink is okay; the only thing that’s not okay is Nazis. Which…right? Didn’t World War II happen?

Sam Gross was born in 1933, an American Jew, and like Woody Allen I’m sure he felt that but for an accident of geography he would’ve grown up to be a lampshade. This stark realization runs throughout his stuff, and I think if he had an origin story, this is it. I suspect he felt the shock, the horror before age ten, maybe even five. I had similar feelings about being disabled. Sometimes circumstances mean you can’t avoid seeing humans for what they are—smiling potential monster-machines—and the question is: what then? Sam turned his shock into art, and a signature brand of profanity-coated compassion. That is, unless you were trying to screw him, or were a fucking Nazi.

I say this is right, and I say we need more of it.

• • •

The fact that our culture has refused to follow Sam’s lead—that we’re suddenly demonizing (of all things) drag queens and allowing, even celebrating, shysters and failsons and Nazis—is probably why Sam stuck around as long as he did. I’m sorry we seem to be replaying the Thirties, but I’m thankful I had so much time with him. Sam Gross was a blessing to me, a profoundly kind, funny, generous, talented man. I did nothing to deserve Sam’s love, but I so appreciated he gave it to me anyway. I hope he knew that. I think he did.

In prepping for this obit, I looked at Rick Meyerowitz’s wonderful book, Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead, which reprinted a cartoon Sam did for The Lampoon. I’ll let you read it for yourself below.

Who else would think of that joke? Who else could possibly pull it off?

There’s a Sam Gross-shaped hole in the world now, and inside me, too. So smart, so unique, so dirty, so sweet—so long, Sam. Your check is in the mail.

You can trust me.

Thanks for this great memorial. You’ve captured him perfectly. Sam is my uncle and part of my life since before I can remember. Missing him 💔 and grateful for your tribute.

That''s a tough one. Putting aside the fact that Sam Gross was pretty much a one-off, I can't think of anyone at The Nib that even does single one-panel gag cartoons. There are a ton of fantastic cartoonists and writers at The Nib, it's just a different thing all together. A different world, a different time. The New Yorker isn't the goal, it's writing a graphic novel. I'm not saying the art of the single panel joke is dead, but it would take me 12 panels crammed with 20 jokes to get anywhere near what a Sam Gross accomplished with a man, a cat with a whip, and a seven word sentence.