I’m happy to announce that yesterday we launched Bystander Academy, a online class hub run by The American Bystander. It’s amazingly cool—and a natural extension of our mission from the beginning.

Bystander was launched for a simple reason: to match our wonderful contributors with their fans, i.e., the audience who will pay for their stuff. In a world of free content, this takes constant effort on our part, and classes are another way to get our geniuses paid.

Bystander Academy is even more important as a way to spread knowledge. We’re committed to preserving the kinds of culture that corporate media doesn’t like—but that audiences still want. (Like print humor magazines, for example.) Our belief is that audiences exist for many more things than the limited options on offer—classes included. I don’t expect we’ll be competing with your local improv school. I’d like us to teach really weird, really unique, really useful things. Stuff our contributors are experts in.

Now that the backoffice stuff is all set up—and you should go look—I want to ask: what classes would you like? Who would you like me to get to teach? I am maddeningly persistent, and highly persuasive, so don’t hold back. Our two offerings—me on longform parody, and General Manager Laura Fox on social media marketing—are just the beginning.

My class starts June 26, and I’m stoked. Like, having a hard time doing the magazine, because I’m thinking about the syllabus. Like, going to Spider-Man Across the Spider Verse and thinking, “This has elements of parody! WE MUST TALK ABOUT THIS IN THE CLASS!” So if you’ll forgive me, we’re going to talk a little about it now—after a bit of background.

When I was a youngster, parody was considered low comedy, fit only for college kids and adults of slightly ill-repute. Woody Allen, for example, was perceived as more intellectual because his movies only had elements of parody—say 20%—and spoofed high-toned things like Russian Lit. Whereas someone like Mel Brooks wore his affection on his sleeve, and lampooned stuff everybody knew about, Hitchcock and Westerns and Frankenstein. Both Animal House and Airplane! were considered classics, but Animal House was a wee bit more worthy of praise because it wasn’t overtly parodic. (Though if you squinted, you could see an intertextual relationship between it and American Graffiti.) There was something, well, cheating about parody, and comedy snobs valued Holy Grail more than Life of Brian because, well, “they stole the story from The Bible.” But that freed them up to talk about lots of things, like the Judean People’s Front or the theory that Jesus’ father was a centurion. Seventies parody was smart.

The rules of much of our contemporary comedy were set back in the 1970s, and in the 1970s, the smartest, most influential parodies were of specific originals. Think of any issue of National Lampoon just loaded with specific parodies, or The 1964 Yearbook Parody, or Life of Brian or Young Frankenstein or The Groove Tube or Kentucky Fried Movie or even Airplane!

But then something happened: our postwar monoculture began to fragment. This is a huge topic which I’m going to sum up in three words, audience choice exploded. Brooks and Wilder could pull off Young Frankenstein because everybody in 1974—whether you were 8 or 80—had seen those movies. My grandma saw them in the theater in 1931; my Aunt had seen them on TV in the ’50s and ’60s; and I’d seen them on TV in the ’70s.

But starting around 1980, the three TV networks were joined in your head by cable; the Midnight Movie was joined by whatever you could rent at your local video store. Suddenly what Person A knew or was thinking about was vastly different than Person B. (MAD Magazine, with its spine of specific parody, never recovered from this.)

In 1990, it was much more difficult to predict what a prospective viewer or reader might know or feel strongly about; by 2000, it was impossible, especially if your material was appearing on the internet. The 1970s were a golden age for parody for lots of reasons, but the basic one is this: you could predict very precisely what your audience knew, what they cared about, and how they’d react. The approach of Young Frankenstein—hip about drugs and sex, overtly campy—was tuned to reflect the shared experiences and attitudes of its main audience, the Baby Boomers. And Wilder and Brooks and all the rest, whether they were Boomers themselves or slightly older people liberated by the Sixties, had no trouble making a unified, beautiful parody crammed with jokes that kill.

Similarly, The 1964 High School Yearbook. Similarly, This is Spinal Tap.

The only thing you can say about my generation, Gen X, is that we resented being lumped together, and our lived experience—of high school, of metal bands, of media—was diverse. But because we particularly mistrusted authority, and cut our teeth on the great parody of the 1970s, we loved parody, and our Gen X solution to this was The Onion. Rather than being a parody of a specific item, it used a general format as a container for a parody of everything.

I’m going very fast here, and I’m going to get into all this in more detail in the class, but The Onion is a brilliant solution to the problem of audience diversity. Each article is an opportunity to connect with a particular reader’s knowledge base and sensibility; if you don’t get one headline, they have 30 others. Plus, it was endlessly refillable: Instead of parodying a specific original, or assuming broad similarity of background or experience in its audience, The Onion used parody as a Trojan Horse, sneaking in every kind of joke about any topic in the bland format of a McPaper, or a website, or later, BuzzFeed.

The Onion also solved another problem, what I call “the Great Lawyering Up.” Consolidation in publishing, both production and distribution, had made it more difficult to parody any specific original without getting sued. At the same time, certain slabs of corporate-owned IP were becoming all we held in common as a culture. If you wanted to do a parody for a mass audience, they might not know the Old Testament or what it’s like to go to college, but they’d certainly know about the Kenobi-Vader lightsaber duel in Star Wars.

There began a certain consolidation of imagination, with a limited set of “worlds” generating bigger and bigger fandoms, who were treating every detail of a canon like Holy Writ. Most importantly of all, they were making Star Trek, or The Beatles, or Star Wars, or Harry Potter an essential part of their personalities: “Who am I? A Han Solo guy.” Teenage fandom began being replaced by a permanent superfandom, as seen in places like Comic Con.

These people were, and are, the perfect audience for specific parody—but owners of IP were very, very paranoid, and pointed lawyers at each other in a kind of Mexican Standoff. The late 1980s and 1990s were a weird time; though the legal protections of the form had been conclusively affirmed by the Supreme Court in Hustler V. Falwell, print parody of specific originals was in decline. What was the point of writing it, if you couldn’t get it published? When the Estate of Margaret Mitchell sued The Wind Done Gone (2002), it was clear that no distancing from the text, no satirical intent, would stop corporate lawyers determined to control any public interaction with their property.

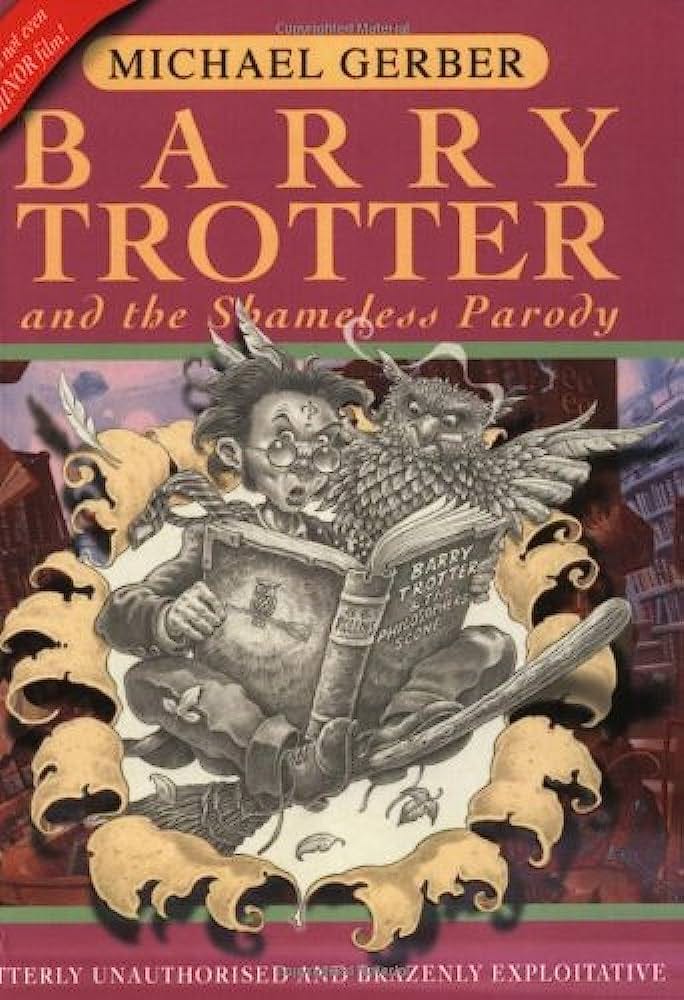

That’s why I self-published Barry Trotter. Harry Potter was that rarest of things, a worldwide phenomenon which was a book. A parody book would have robust protection, and could be produced by an individual (rather than a movie or TV studio). Barry Trotter was my test-case for a lot of theories and beliefs about parody—how it really functions with modern audiences, not how corporate lawyers looking for billable hours think it does.

Barry Trotter turned out to be a watershed book in the history of parody; unlike its closest ancestor Bored of the Rings, it was not authorized—but neither the author nor Warner Bros., the owners of the film rights, chose to sue me. I cannot speak as to why, but I suspect that they realized that parodies in general, and my book in specific, actually deepened fan investment in the original property. (I remember sleepily asserting this in interview after interview, with radio DJs from Leeds trying their best to get me to say I hated Harry Potter.) In the wake of Barry Trotter’s worldwide success, corporations were slowly learning that fans were interacting with their properties differently than they realized. Barry came out between HP4 and HP5; and HP5 sold spectacularly…featuring several shout-outs to my parody in Rowling’s text. In retrospect, after Barry Trotter the next step was inevitable: faced with knowledgable, self-aware fanbases hungry for more content, corporate IP holders have themselves begun to use parodic techniques in their authorized, canonical works.

And now we come to Spider-Man: Across the Spider Verse. The basic premise of this latest addition to the Marvel franchise—that our Spider-Man isn’t the white, bespectacled Westchester teen Peter Parker, but Miles Morales, a 15-year-old New Yorker of Puerto Rican descent living in Brooklyn—is fundamentally intertextual. Our opinions about this new version of the Spider-Man story (the sense of freedom, of currency, of inclusion, of gentle satire) are generated by its relationship to the earlier text. Multiverse’s retelling is even slightly parodic, in that it is slyly critical of the original—how narrow Lee’s original story seems! How whitebread! It flatters the reader’s intelligence, as parodies always do, and sets up our modern viewpoint as inherently wise and correct.

When I made Barry Trotter a layabout, loathe to leave Hogwash because he liked being a B.M.O.C. and knew that his life would likely never get better, I was applying precisely the same kind of thinking as on display with Spider Verse 1-2. And, were I a writer employed by Rowling, Inc., today, tasked to come up with more I.P. to keep the theme parks full, I’d employ my parody-brain to generate stories—making Hogwarts feel large, messy, contemporary, a Potter for every sub-audience. And the how (a spell, a multiverse) is just the macguffin. Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse is nearly three hours of exploring an intertextural, constantly self-referential, frequently parodic world. It’s the Spider-Man you thought you knew, only different, inherently a comment on the past—a story written for the wants and needs of fans in 2023, clothed in a 60-year-old story we all know, one of the few stories we still all know.

As you can see, I can talk about this forever—and as you can also see, a class on parody structure is a good idea for anybody wanting to write mass-market stuff for contemporary audiences. If you want to work with the keepers of our modern religions, those ever-shrinking number of vast corporations, a thorough grounding in parody is essential. Anybody who has been intrigued, check out the four-week class here. It will be the first of many, thanks to Bystander Academy.

I’ll speak to you again Friday.

Something clicked in reading this, and I think I finally understand what you've been trying to tell me about parody as a container over the past few years.

I’m probably just saying something you said already, but with different words. For me the great thing about parodies like high school yearbook and airplane, and both python films mentioned, and young Frankenstein, is that the parody is not a restraint on places the comedy can go. In fact, it may be the weakest or least memorable aspect. It also provides dramatic structure, perhaps the toughest thing to nail with comedy storytelling. And it seems less contrived than grafting comedy onto a conventional Hollywood formula; it’s by definition mocking something, so it’s less open to mockery itself than a rom com or action film might be.