[As Bystander #26, our first Cartoonists’ Annual, goes to press, I’m reprinting my Publisher’s Letter. Enjoy.—MG]

If a group of crows is a murder, and owls a parliament, around Bystander we call any collection of comedy writers a “kvetch.” The same, apparently, could be said of one panel cartoonists—on Page 9 there begins a roundtable which is gloomy in the extreme. But who can blame them? We are now fully half a century past the heyday of general interest magazines. and on top of that injury crouches the insult of the internet. While we now know that the web cannot do what it was invented to do—keep the populace safe and sane in times of catastrophe—it has shown itself to be truly excellent at killing any type of for-profit publishing.

And what about AI? Could it be trained to create one panels? Probably—but I say it’s spinach, and I say 10101010.

So you’d think, in our capitalist utopia, where each of us is a rational actor driven by economic self-interest, this would spell a mass exodus from the form. Not so! Thanks to social media, gag cartoons have never been more widely enjoyed, and more people are drawing them than ever. And this too, according to the group, may be a problem. Instead of being driven by jokes, which are hard to think of, time-consuming to execute, and often offend, too many contemporary gagsters aim for a gentle spasm of self-recognition—the pithy depiction of an annoyance or minor social ill that makes the reader think, “Yes. This, too, has happened to me.” While few of us have the knack for great jokes, all of us have met someone who can tie a cherry stem into a knot with their tongue.

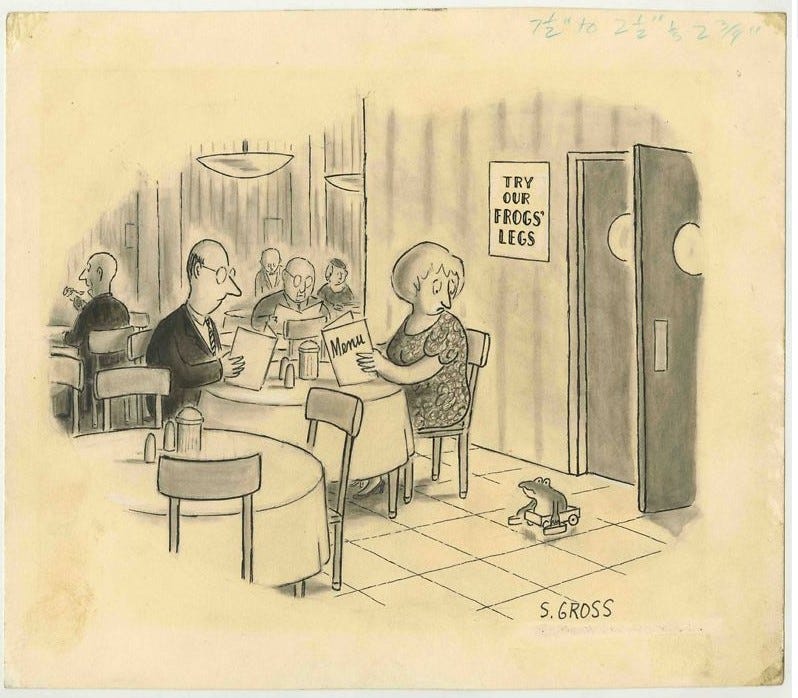

I genuinely love cartoonists, and adore the modern one panel cartoon, where the joke lies in the interplay between the art and the caption. That delay in perception—the “putting it together” that is required of the reader—turns the whole thing into jazz. At its best, a one-panel can confer a kind of immortality, if only for a generation or two. Such a gem has to be really funny, of course, but also has to be unique to that artist. Sam Gross’ “Frog Legs” cartoon couldn’t have come from anyone else.

I have a theory—and please note that Sam is no longer here to say, “Ahh, you’re full of shit”: I think the modern one panel is a profound expression of individuality, and that it—like the modern short humor piece—was born in the wake of World War I. WWI, and later, the Depression, were powerful reminders of the folly of groups; this is why the first crop of one panel geniuses seem to come in the ’20s and ’30s, followed by a second crop in the ’60s and ’70s. This second group is passing now, and there is no publishing industry left to nurture a third.

The true geniuses aren’t selling “gags.” They’re presenting a whole worldview, unique to themselves, undrawable by any other hand. Throughout our culture, intense personal expression via mass media is growing rarer. Novelists are no longer central; ditto rock stars. Most of Hollywood’s auteurs are from a different era—people like Scorsese and Coppola will not be replaced, any more than Kubrick was. In TV we are hopeful about the strike, but the death of streaming doesn’t augur well for the star showrunner. Cartooning is intimate, the product of one unique soul beavering away alone. This is why the recent deaths are so hard—there’ll be wonderful cartoons in the future, but no more glimpses into George Booth’s world. Or Sam’s, or Jack Ziegler’s, or Ed Koren’s. The lions that are left, people like Mort Gerberg and Sidney Harris, not to mention spring chickens like Roz—I wish them low cholesterol and great health insurance. In the meantime, Bystander fights on.

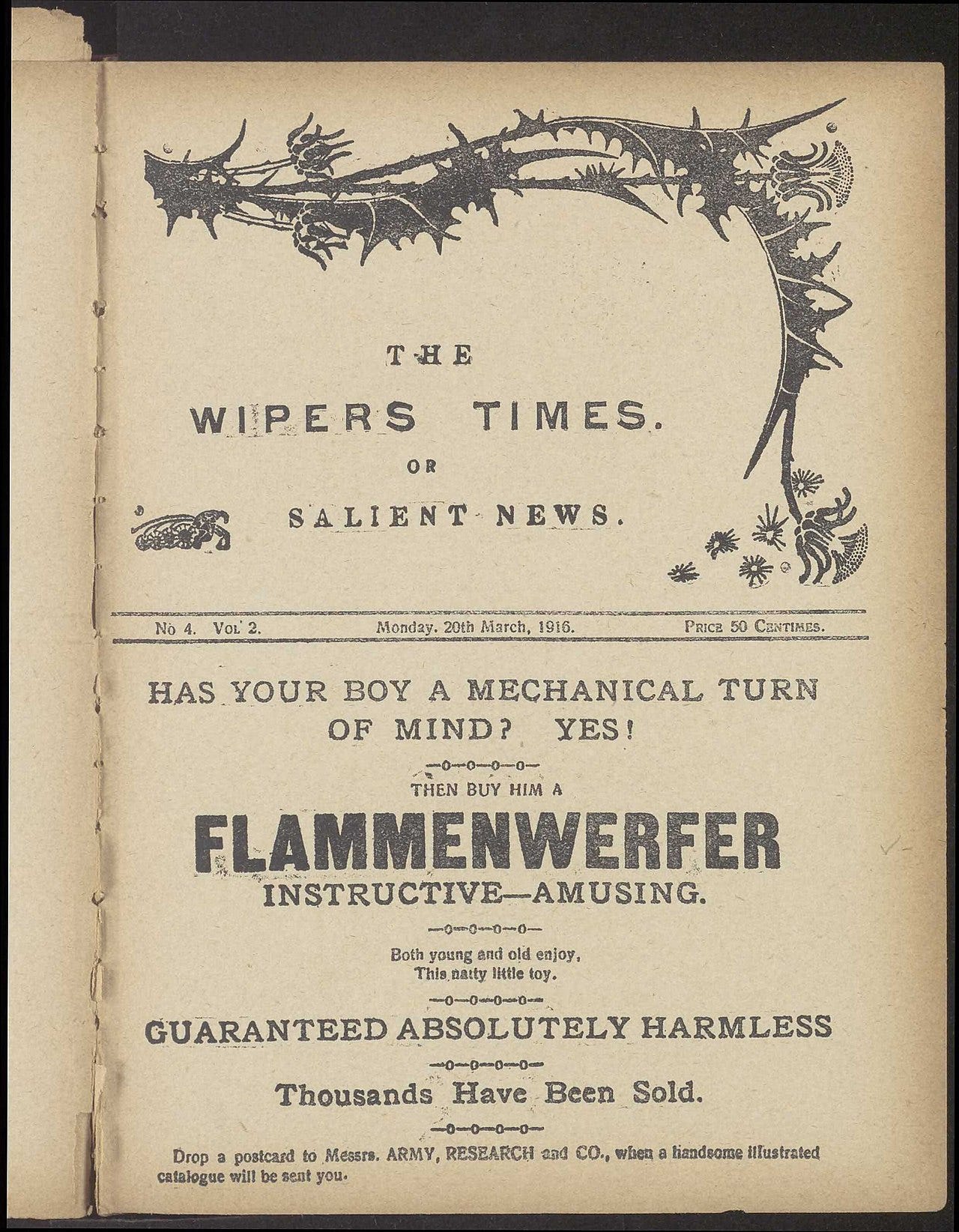

We fight because we will win: Whenever I hear a dire prediction, humor-wise, I think of The Wipers Times. Published by British soldiers stationed in the trenches of the Western Front, this humor magazine sprang to life when some Tommies found an abandoned printing press. They decided to publish a journal of war humor, fake ads, cartoons and (this being World War I), poetry. The Wipers Times—named after how the Brits pronounced “Ypres”—began in February 1916. It lasted, despite shot and shell and mustard gas and bad poetry—until after the war’s end.

If a print humor magazine can survive all that, one panel cartoons can survive a Charles Addams-bot. Lately I’ve been thinking that the internet itself may not last much longer in its current form; the centrifugal forces it unleashes may be simply too destructive to countries’ political systems and societies. There is nothing permanent or inevitable about our current situation, and this era of Tycoons Gone Wild may well be looked on, after its end, as a time of collective madness. Some bad idea we all stumbled into, hoping for the best, never thinking it would get this terrible, something awful that had to run its course. Kind of like World War I.

So let us take a moment to salute the Tommies in the trenches of today, young and old, gamely producing cartoons for our amusement and little remuneration, racking up “likes” and sometimes even immortality (of a decidedly temporary nature). Let us read magazines like this one—and encourage friends and relations to buy subscriptions, hint hint—all straining towards the day when peace is declared, heroes are honored, and life returns to normal.

The Pergola des Artistes may have been killed by COVID, but the Tuesday cartoonists’ lunch never ends. Ask not for whom the “kvetch” convenes dear reader, it convenes for thee.

Thank you for writing this, Mike. Just when I start to get too depressed about my cartoon scribbling, you manage to help lift my spirits to continue on this road. Now as to whether this trip is on "The Road to Abilene" I guess we'll leave to future generations to decide.

But this is why magazines that collect humor, such as the American Bystander, are so damn important. Future archeologists and historians, even if they happen to be highly evolved, irradiated cockroaches, will appreciate the truly timeless single panel cartoon.

Bonus points for the "I say it's spinach" reference. Much appreciate it.