The question was asked: “You told me you used to fence. Would you tell us about it?”

For about three months in 1995, I attempted to learn how to fence, courtesy of the Seattle edition of The Learning Annex. But just as I started to get the hang of it—just as I started to think that maybe, somehow, with a lot of practice I might get good—I stopped.

Why did I do that? I love combat sports; ten years of qigong has taught me that I approach everything like a combat sport. Was it the cerebral palsy? Well, I did get frustrated—fencing with CP is like wearing those old-fashioned ski boots. You’re always up on your toes, with your feet so so heavy and balance precarious—but I have quick hands and a strong will, I could’ve figured out a strategy. I adored it all; the heavy mask that reeked of sweat and fear; the heavy duck chest protector that came up from the groin and fastened around the side with Velcro; and most of all the foil itself, which smelled like pennies and made this marvelous shiiiiing when you advanced on someone, blade on blade.

So why did I quit? That’s a bit of a story.

• • •

It’s very difficult for me to be the real me. I can feel him in here, chattering away, a fun, happy fellow interested in everything and afraid of nothing. But every second, a weird kind of gravity pulls me down towards a lousier, more burdened, blander version of myself. I hate it. I fight against it. For example, I just drank some srihacha straight out of the bottle like a suckling hamster, because I needed to feel something.

The further West I go, the weaker this downward pull seems to be. I currently live in Santa Monica, and am about as content as I can be without getting wet. Even the things that most people hate about SoCal, I blatantly enjoy. Crystal shops. Strange religions. The occasional small earthquake. Wheee![1]

The first time I made the trek West was July 1994. I had been living with my parents in Oak Park, Illinois for the past year, working a job downtown, gathering funds for another assault on New York. For the first time since Kindergarten, my future was raw and unformed and to my surprise, I rather enjoyed that.

Around my 25th birthday, my best friend Jerry called. He and his wife had moved out to Seattle, where they both were going to grad school at the University of Washington. “When are you coming back home for a visit?” I asked.

“Never.” Jer and I had gone to high school together and Oak Park, though a nice town, had been the site of unhappy times for us both. “Why don’t you come visit us instead?”

“Ah, nah.”

“Why?”

“Jerry, here in the Midwest, we don’t do spontaneous non-work-related travel. Especially for pleasure.”

“I’m buying you a ticket.” Jerry was from the Midwest too, so he knew he’d checkmated me; it would’ve been rude to say no.

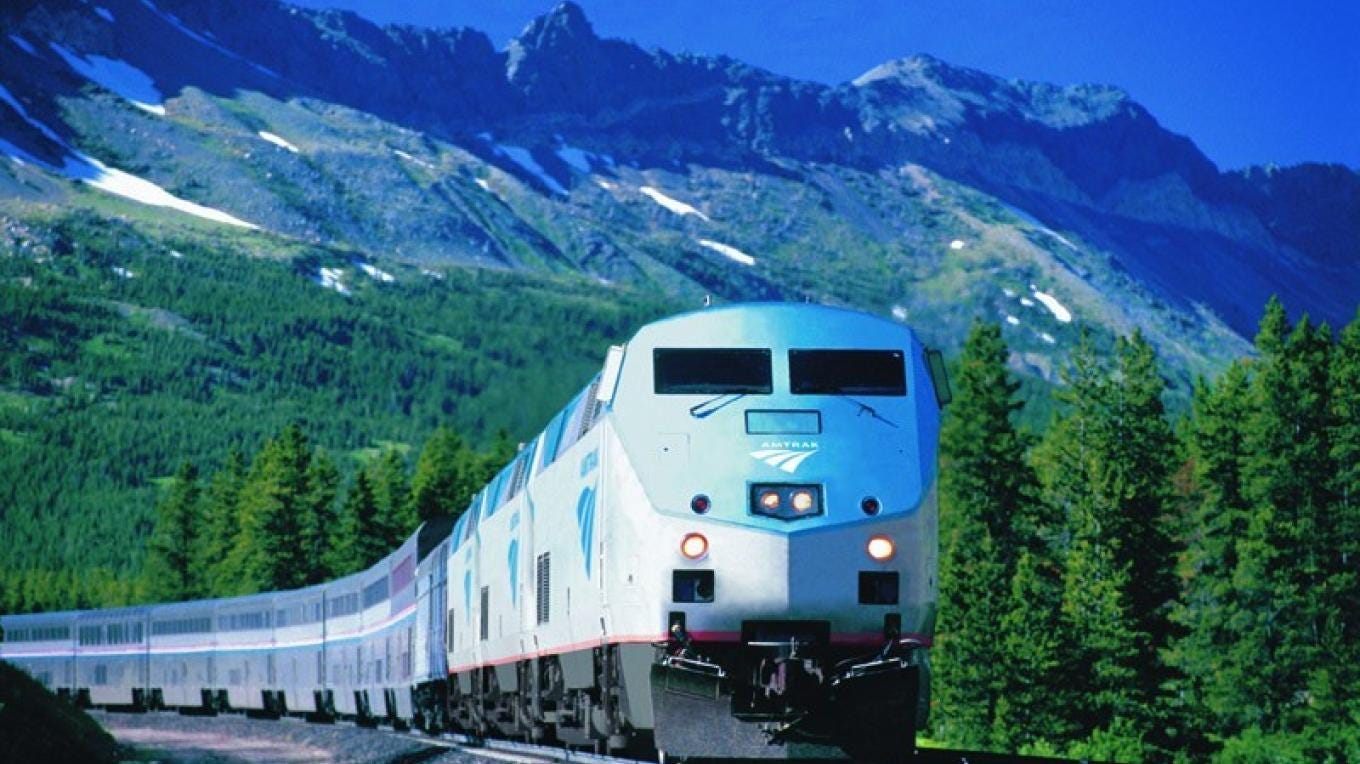

With Jer covering my trip back, I decided to go out by rail. The trip took two and a half days, and I adored every minute. I’d never taken a long train journey, nor had I seen the country west of St. Louis. I took the Empire Builder, the Northern route that chugs up to Milwaukee then over, across the Great Plains and through the Rockies, then finally through Montana and Glacier National Park to Seattle.

With a young man’s titanium ass, I toughed it out in coach. When I needed a stretch of the legs, I walked back to the bar car—where, somewhere outside of Minneapolis, I met a young curvy blonde. I don’t remember her name, but I recall that she was pretty and 27, and going out to see a girlfriend in Portland. A girlfriend girlfriend? I never found out, to my everlasting regret. But she taught me a great card game called “rummy” that I play to this day. It’s like North by Northwest if Eva Marie Saint didn’t seduce Cary Grant, merely took $14 from him, one penny at a time.

Jer and Whit were no dummies; there’s no place more attractive than Seattle when it’s sunny, which is to say, July and maybe part of August? For all I know global warming has turned it into the Mojave, but back in July ’94, we three spent a week talking and laughing and picking raspberries that grew on bushes right on the street. By the end of the visit, I had decided to move there—just for the year before I went to grad school. I didn’t want to do anything crazy, like derail my career or, you know, achieve a deep and lasting contentment.

After staying with Jer and Whit for a few days, I found a little basement studio apartment in a big building on the corner of Broadway and East John Streets. God knows what lies I told to get the place. Then again, the super was a soul patch-sporting jazz saxophonist who spoke in an impenetrable hipster patois—he actually asked me once, in all seriousness, whether I was planning to get “some slickum on my hangdown this weekend.” So maybe the bar was pretty low?

It needed to be. Bohemian Seattle was in its full grunge-powered flower, and Broadway is the main drag of Capitol Hill, Seattle’s gay neighborhood. Thirty years ago the area percolated with artists, writers, musicians, and others of strong aesthetics and uncertain employment. Speaking of aesthetics, my apartment was beyond sparse; though it was clean and well-maintained, my idea of furnishing a place was a mattress on the floor and a bowl with two goldfish, which I named Castor and Pollux. A shoe store down the way was closing, so I salvaged some glass panes and metal brackets from a display; I fashioned these into bookshelves, then filled them with used books from across the street. For décor, I found a photo of S.J. Perelman—the famous portrait by Ralph Steiner—and took it to the Kinkos on the corner. I had them blow it up, then laminate it. I tacked it on the wall above my bed as inspiration, a companion, a protecting spirit.

I did not have a television; if there was something I needed to watch—Michael and Scottie, for example, and if you have to ask who they were you were not a male alive in 1994—I could go to a sports bar down the street. On weekends from August to February, the football games started at ten in the morning, when they would throw open their doors and let the sound spill out onto the street. This thrilled me; the place felt as naughty as a brothel, with its football all day.

When I had money, I could walk down to the Harvard Exit movie theater, or head down to a storefront on Pike Street, where a man showed 35mm prints on a bedsheet in the back room. Art-house stuff, sleaze and exploitation, old commercials, government scare films—stuff you couldn’t easily see, before the age of the internet. When I didn’t have money, even the people walking by my basement windows were a constant source of entertainment. I am sure I saw the top of Kurt Cobain’s head.

I was deeply, deeply content. My expenses were low, and with the tech boom, temping was plentiful. I remember working for a big biotech firm, Immunex, and of course Microsoft, where Jerry would work after grad school was over. The fellas at MSFT thought they were buying me cheap by giving me all the Hot V-8 I could drink, but I couldn’t have been happier as I designed their presentations. I’d work an assignment for a while, then when it was over, live like artists always have, upside down—sleeping late, prowling bookstores and coffeehouses until nine or ten p.m., then reading and writing all night. I still do that. I’m doing it right now.

In a neighborhood full of characters, I slotted in immediately. Within six weeks, they knew me at the Dick’s Drive-In, in all the used bookstores, at the Kinko’s across the street. I was working on a big parody of The New York Review of Books, which I’d lay out until all hours of the night. I learned that if I printed out an extra copy of whatever page I was working on, and gave it to the girl behind the counter, she’d “forget” to charge me.

“This is really funny! What are you going to do with it?”

“I don’t know,” I said honestly. “Send it to the real New York Review? Maybe they’ll give me a job.”

“They totally should,” she said, both of us knowing they wouldn’t. The kind of person that worked at The New York Review of Books wouldn’t be designing some crazy project at 2:30 a.m.

“What is that called?” I asked, pointing at the small titanium bolt piercing the delicate partition between her nostrils.

“I don’t know, but it itches.” She squinched her nose and brushed it with pursed kissy lips. “I think it might be infected.”

I had a big desk made of two-by-fours that I’d inherited when an architect down the hall moved out; and in front of that I’d strung heavy wire, from which I’d hang pages of the NYREV parody as they were completed. I’d gotten an overstuffed gray couch, which Jer and Whit had helped me lug from a dirt lot in Renton, 45 minutes away. They were such good friends, God knows why.

I was already quite sick, and getting sicker—yet Jerry would always call me, or bike over after class. I couldn’t go far from my house, probably four blocks was my maximum—so we’d hang out at the coffeeshop, or if I was feeling well, bus over to the U district, where there were yet more used bookstores, and a theater that showed old movies.

I loved how clear the air was in Seattle, how bright blue the sky, and how when I walked out my front door, there was Mount Rainer looming. This was before The New Yorker ran that piece about the impeding destruction of the PNW by earthquake…or was it supervolcano? None of this mattered on Cap Hill, where shirtless guys and occasionally gals would cruise each other, then head down Broadway towards the park for some anonymous sex. People were staring down AIDS; what was another cataclysm to them?

I suddenly feel sheepish; I am sure many people have written about this time and place better than I could—Dan Savage’s paper The Stranger, for one thing, was pole-axingly well-written. The Stranger of 1994-95 was to alt-weeklies what The Onion became to comedy, a kind of Platonic ideal. When you read that paper, or saw a play in a storefont theater, or went to an art exhibit in a nearby warehouse—not to mention all the bands playing out and in—it was clear this was someplace special, in a special era. Seattle in the Nineties was, I suspect, very much like San Francisco in the Sixties—right down to the junkies sprawled in doorways. I stepped over a lot of kids, a lot of runaways. As in the Haight in late ‘67, there was a fine line between perfect ripeness and the beginnings of rot.

Jerry and I spent hours and hours in Café Roma, playing the card game that woman taught me on the train. (Jerry also beat me. I guess I’m not very good at rummy.) Fifty feet from my apartment, Café Roma was the kind of coffee house you just don’t see much in the post-Starbucks era—a genuinely funky, locally owned place, the walls crammed with art by local exuberants of questionable talent. The baristas at Roma, people like Miss Savage, a pixieish brunette with a gravelly voice and a gentle demeanor, had tats and piercings back when tats and piercings really meant something.

That section of Broadway bustled, and Roma was the center of it. Everybody came through for coffee tea and sympathy, and if you planted yourself at a table, eventually whoever you were looking for would amble in. Its bulletin board was Capitol Hill’s samizdat. One terrible night, Roma was its sanctuary too. Twenty five years before the cops busted up the CHOP (Capitol Hill Occupy Protest), a peaceful march on Capitol Hill turned into a police riot; Savage and a bunch of us regulars all watched from behind Roma’s plateglass, grabbing kids and yanking them inside before they got a nightstick or a boot to the head.

Three years after the flu that wrecked my immune system, my stomach was turning from a reliable body part into an unpredictable source of pain and embarrassment—a torment. To his immense credit, Jerry never complained, never judged, and never dropped me. He and Whit even cooked dinner for me, a thankless task that was getting harder by the week. We laughed so much that whole year, more than I ever have before or since, and played football and frisbee in the park. And the days I didn’t feel well, we’d just stay indoors playing cards. I’d taken to drinking soymilk lattes with mint flavoring, which gave the pint a pale green viscosity that Jer called “Mike’s milk of magnesia.” One weekend, we went to a video store and rented eight tapes of “The Men Who Killed Kennedy,” a documentary series which aired on the History Channel once, then was pulled after a huge controversy. I don’t think Jer was particularly interested in the JFK assassination; I think he just loved me.

JFK was dead and my stomach was killing me but somehow, tucked away on Capitol Hill, everything seemed okay. I was happy; so why in the hell did I apply to NYU? And what about fencing?

• • •

One afternoon in January 1995, right around the time my application was sent in, Jer and I were sitting in Roma, drinking coffee. He was reading linguistics for school, and I was browsing The Learning Annex, which I put down on the table with a slap. “That’s it,” I declared. “I’m taking up fencing.”

“You mean, like posts?”

“No like en-garde,” I said, miming.

“Where did this come from?”

“From my unquenchable desire to bring every man to heel,” I said. “You shall recognize your betters, Jerrod.”

Jer put down his textbook, and picked up our worn deck of cards. “Guess I’ll have to beat you again,” he said wearily.

• • •

About two weeks later I stood in a gym near downtown, pointing a foil at a young woman. What she knew is that I’d practiced my parrying—“one, two, three, four”—obsessively since the last class. What she didn’t know is that I was wearing a cup for the first time, and it was really binding my scrote.

Must—not—readjust—my—in—public—

I felt a sharp poke on my shoulder. “Hit!” she cried.

Pissed off, I grabbed my cup, and yanked it into place. Then I focused up, and made sure she didn’t score another touch for the rest of the class.

“You’re improving,” the teacher said. He had a large, droopy moustache and spoke with an accent of indeterminate European origin.

“Merci,” I said.

“Your legs, remind me the problem?”

“Cerebral palsy,” I said. “Just pretend I don’t have them, I try to.”

I basically had my choice of two strategies: to berserker attack and back my opponent into the rear portion of the mat, or lay back and let them come to me. I learned not to flinch when my opponent lunged, and my parrying was getting better. My cerebral palsy made moving just too slow; there was a good half-second between my brain shouting “MOVE!” and my legs doing anything. And when they did move, it was with the speed and precision of a teenager cleaning their room.

“You will never be able to compete, I’m afraid,” my teacher said.

“It’s not them I’m competing against,” I said. I stalked home, the long gray bag over my shoulder. Who was he to tell me I’d never compete? I’d show him! There had to be a way! If I could get into Yale from Ballwin, Missouri, I could certainly outsmart some asshole that looked like he was in Bachman Turner Overdrive.

For a few days, I kept practicing. Then, I got the letter that I’d been accepted to a Master’s in Publishing at NYU.

The next day, I quit the class.

• • •

Why did I quit? I loved to fence, and I’m sure I could’ve come up with something to compensate for these clumsy legs, stiff and tired since birth. Now, after ten years of qigong and some other martial arts, I know that with the right teacher, I might’ve even been able to compete.

And the fencing really felt like me, you know? Much more than New York ever did, or going back to school, or the goddamn publishing business. What did I want with New York anyway? I’d lived there already, and it was nothing but tenseness and terrifying phone calls and rejection. I think maybe it was because I’d been praised so much for my brains, and had so much early success wrangling words, that seemed like a safer bet than simply being happy. I rejected who I was, for who I thought I should be.

I left Seattle almost exactly a year after I’d moved there, in August. But before I did, Fate gave me one more chance. For reasons a bit too complicated to go into here, I had been offered a gig writing reviews for a local startup named Amazon.com; I’d passed the audition, my editor said. “Would you like to come on full time?”

“Can I have a day to think it over?” I asked.

“Sure,” she said. “But remember, this is tech. We want to move. You come on board, you’ll work hard but rise fast.”

“I’ll tell you by tomorrow,” I said.

I was really torn, so on a whim I walked down to the place that showed movies on a bedsheet. They were showing La Dolce Vita, one of my favorites since I’d seen it in college. I related to Marcello, the smart kid from the provinces who moved to Rome to make it as a writer, an ambitious, strangely aimless man in search of the sweet life.

As I sat there in the dark, munching some Junior Mints (the only candy that wouldn’t make me sick), I struggled with my decision. I had a pretty sweet life here in Seattle, but it was small—where was the money in it, the glamor? As much as I wanted to stay, I couldn’t get sidetracked writing copy for some dopey online bookstore. I would go back to New York, go back to the magazine business, because I wanted to be big, wanted to be a star, wanted that La Dolce Vita.

The next day, I told my editor Katherine of my decision. She asked me to reconsider; she might’ve even said, “stock options.” But I was too ambitious to be moved; New York was where fortunes were made, so it was to New York I would go.

I remember the first time I watched Fellini’s masterpiece. I was a freshman at Yale and with an ass of titanium, hadn’t taken my eyes off the screen for the entire three hours. One of my classmates buttonholed me at lunch the next day.

“What did you think?” he asked.

“Oh I loved it,” I said. “I wanted to be Marcello.”

“Are you kidding?” he laughed. “Marcello was miserable.”

“I know,” I said. “But he looked so good.”

POSTSCRIPT: In 2019 I flew up to Seattle for Jer and Whit’s 50th birthday. We played a little rummy. While beating me—as is traditional—Jer remarked, “Capitol Hill isn’t what it used to be.”

“Will it make me cry?”

“Only one way to find out.” We drove over and sure enough, my funky old neighborhood had been turned into a canyon of condominiums. Some of the old restaurants were there—chocolate is a recession-proof business, and Dick’s too—but everything else was gone. The Condomania killed by PrEP; all the used bookstores; the Kinko’s, of course; even lovely Miss Savage’s Café Roma.

But there in the dusk, I felt the old feelings of possibility, of life and love and art. There was something about the light, so much less intense than the light down here in LA, but Western light nevertheless. The light of possibility, of freedom, of happiness—of true la dolce vita. I turned away from it once, but ten years later, I came West again, this time for good.

And who knows? Perhaps it’s not too late to take up fencing.

[1] “Ironic that Mike died during the Big One. Remember that column he wrote? The one that said ‘Wheee’?”

I love visiting the west coast -- the light, the vibe, the Asian influences, the feeling that there is a WHOLE GODDAMN OCEAN over to the left -- but I could never move there. I am always struck by the feeling that it would've been cooler 40, 50, 60 years earlier, before all the development. This can't be nostalgia, unless I'm yearning for the west coast shown in movies and the Rockford Files. I think it's concern for the ecosystem. Then again, I think there are too many goddamn people EVERYWHERE.

I also moved to Seattle in ‘94. Stayed 25 years. Lotsa changes since.